Saccharin is a “non-nutritive” sweetener– which means that while it tastes sweet, it provides the body with no nutritive value.

Saccharin was discovered and used commercially before 1900. This doesn’t make it the earliest of the artificial sweeteners; it was preceded by sugar of lead, which is just as unhealthy as it sounds. At any rate, it is the oldest of the modern artificial sweeteners.

How do you know something is sweet? You taste it, of course. So it should come as little surprise that a common story in the discovery of artificial sweeteners is that someone tasted something they really shouldn’t have, a situation chemists generally try to avoid.

In the case of Saccharin, the someone was Constantin Fahlberg, the lab was at John Hopkins University, and the year as 1879.

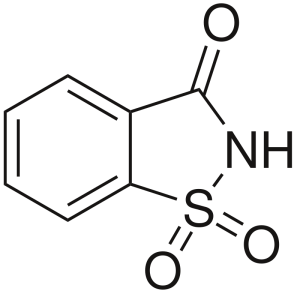

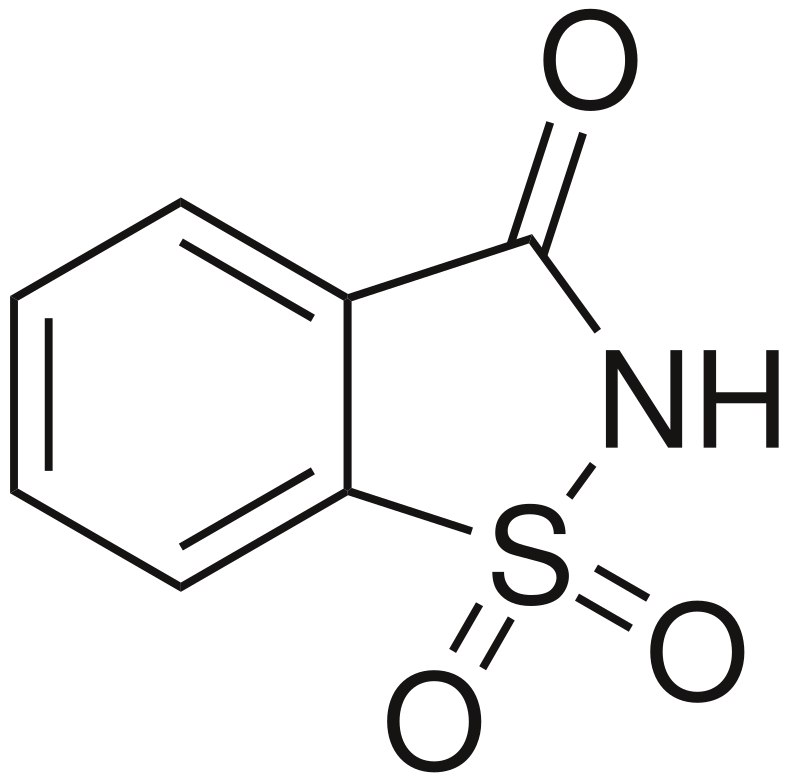

The chemical names for saccharin are sufficiently arcane to the non-chemist, that use of the common names such as benzosulfimide is preferable to the IUPAC name. It possesses a benzene ring, which is a six carbon ring of alternating single and double bonds, as well as a second, rather more interesting ring.

Saccharin became popular during World War I, due to sugar rationing.

Where is it found today? Saccharin is readily found in sweet’n low. It can be found in some medicines, chewing gum, drinks and baked goods. As it has something of an aftertaste, it has been replaced in some instances by other artificial sweeteners.

Is it safe? . As always, the rule in toxicology (the study of poisons) is the dose makes the poison. Anything in sufficiently high amounts is likely to be lethal. That being said, is saccharin dangerous in typical doses?

The earliest form of this question is something along the lines of does it cause cancer? And the answer is, in rats, absolutely. Bladder cancer specifically. It turns out that humans are somewhat different than rats, so if it does so, it certainly does not do so via the same mechanism. The cancer warning label was removed in 2000.

Not causing cancer is a pretty low bar to set for being healthy, though. There are some concerns that are applicable to pretty much all artificial sweeteners- and those I’ll talk about in another post.

There’s a study in which male rats were fed saccharine, saccharine and nicotine, and nicotine alone, then the resulting behavioral changes were studied in the male rats and their offspring. And they did see behavioral changes for just saccharine, and those changes did appear to be passed down from father to child. Now, rats are not exactly like people (as the cancer question has shown), but changes in working memory and hyperactivity certainly suggest reason for further research.

Another important question to consider is efficacy with regards to diabetes. Sugar substitutes are often promoted for diabetes patience as a way to reduce their sugar intake. For an artificial sweetener to be beneficial for insulin resistance, it would, presumably, need to not act like sugar for the body. The problem is that saccharine does taste sweet, and our taste receptors can regulate the release of insulin.

Saccharine does trigger the release of insulin. What’s the consequence of increased insulin (the hormone that tells our bodies to turn sugar into fat) without the presence of glucose? Short term, it should reduce blood sugar. Long term? It seems like insulin resistance would be the logical result, since Low blood sugar is dangerous and something our bodies prefer to avoid.

Are there studies supporting the idea that saccharine might contribute to insulin resistance (diabetes)? Yes, both regarding the mechanism just described and regarding changes in gut microbes as a result of saccharine ingestion. Do all the studies same thing? No, the results are pretty mixed. Some say that there is no effect, others say there is a significant effect.

Leave a comment