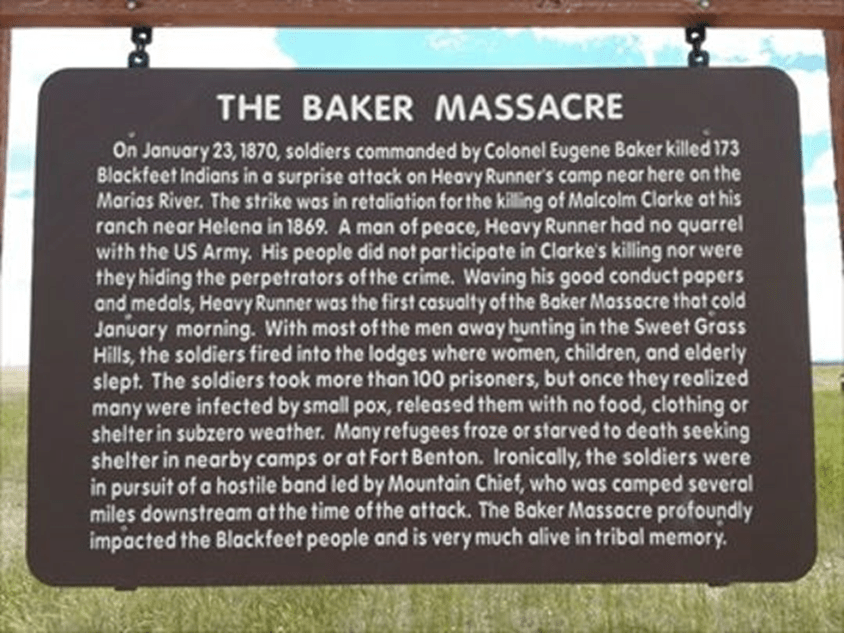

Driving across Highway 2, there is a sign pointing out the Baker Massacre. It occurred in 1870, but has always been a bit hard to research.

The sign perpetuates Major Baker’s reports – as I drove by, I believed the statement that the Cavalry hit the wrong group, but in 1982, Ben Bennett published Death, Too, for the Heavy Runner. There had been a Heavy Runner family in Rexford . . . and I started looking at the stories of the Baker Massacre a bit more critically. Later, a Blackfeet classmate in my master’s program brought a little more contact with the story, a little more interest. Having friends on reservations brings the history a bit closer – makes it a bit more relevant.

If you try a computer search for The Heavy Runner, you’ll probably wind up with a lot of hits on shoes. The Piikuni and the U.S. Army’s Piegan Expedition provides a pdf article that covers the story, and goes into the details that never made the sign by Shelby:

“Near the end of October, Sheridan proposed to Sherman, “Let me find out exactly where these Indians are going to spend the Winter; and about the time of a good heavy Snow I will send out a party and try and strike them” when “they will be very helpless.” Sheridan knew that only “women and children and the decrepit old men were with the villages.” “We must occasionally strike where it hurts,” he added. The purpose of the winter attack was “to strike the Indians a hard blow and force them onto the reservations; . . . to show to the Indian that . . . he, with his villages and stock, could be destroyed.” General Sherman sent word on November 4, 1869, that the “proposed action . . . for the punishment of these marauders has been approved.”18 On November 15, 1869, Sheridan recommended Major Eugene Baker of the U.S. Second Cavalry be assigned to lead the expedition. “Major Baker . . . is a most excellent man to be entrusted with any party you may see fit to send out,” Sheridan assured Major General Winfield Hancock, commander of the Department of Dakota, adding, “I spoke to him on the subject when he passed through Chicago.” En route, Baker conferred with de Trobriand at Fort Shaw on December 22 and continued to Bozeman to take charge of Fort Ellis. Inspector General of the Military Division of the Missouri James Hardie thought Baker “should be allowed to proceed generally according to the circumstances under which he finds himself in his operations,” an opinion to which Sheridan replied, “Tell Baker to strike them hard.” Hardie agreed, writing, “I think chastisement necessary. In this Colonel Baker concurs. He [knows] the General’s wishes . . . [and] may be relied on to do all . . . in the way of vigorous and sufficient action.” Thus, Sheridan expanded Sherman’s authorization to include attacking a camp sheltering any Piikunis and empowered Hancock to extend the order and authorization to de Trobriand and Baker. Sully and de Trobriand discussed attacking a friendly Piegan camp in order to quiet the others, after which de Trobriand lamented, “I cannot honestly say that I regret that no action has been taken on your proposition to pitch into those two friendly little bands.” In early January, de Trobriand ordered Baker “to chastise that portion of the Indian tribe of Piegans under Mountain Chief or his sons.” De Trobriand’s intent was to surprise Mountain Chief ’s camp first and then sweep into bands camped near Riplinger’s trading post and then others farther away. However, he specified that the camps of Heavy Runner and Big Lake—chiefs of the two “friendly” bands—“should be left unmolested.””

Fundamentally, Sheridan authorized attacks on the friendlies – The Heavy Runner’s camp, while Colonel de Trobiand said the Heavy Runner’s camp “should be left unmolested.”

The easiest way to cover the massacre is to quote Henderson: “The U.S. Second Cavalry under the command of Major Eugene Baker decimated Heavy Runner’s camp without warning on January 23, 1870, in what the military called the Piegan Expedition. Cavalrymen shot Heavy Runner and slaughtered 217 noncombatant elders, women, and children. They then destroyed the food supply, burned lodges, and captured four to five hundred of the camp’s horses. Few of Heavy Runner’s people survived. No depredations had been committed by the band, and Heavy Runner carried papers identifying him as being on peaceful terms with the United States. As trader Alexander Culbertson observed, 1870 would forever be engraved as “the year of Small pox and Soldiers.”

“Decimated” seems to be a misused word in this case – The Heavy Runner’s camp had a little over 300 people present. Killing 217 out of 300 people is closer to annihilation than decimation.

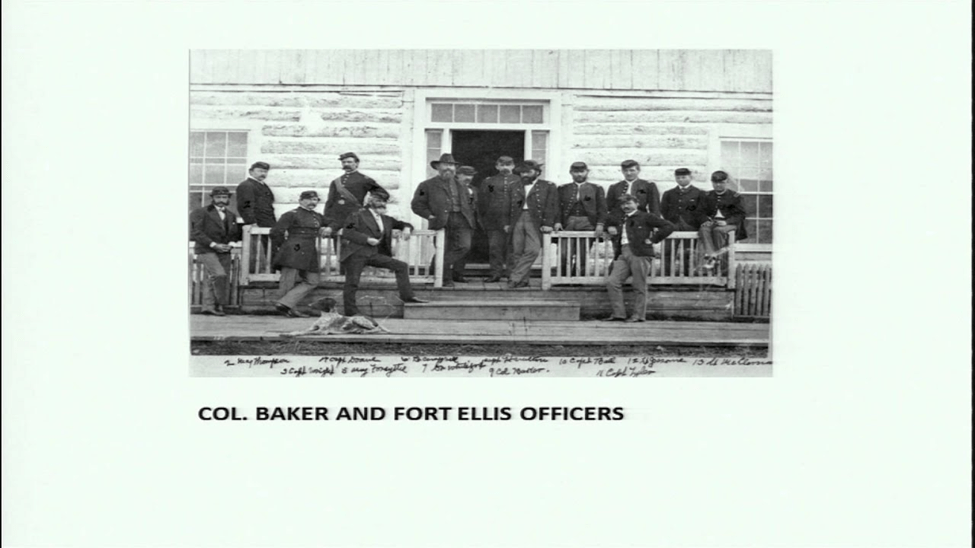

Find-a-grave includes a little biographical information on Major Baker: “Cadet, US Military Academy, 1854/07/01 to 1859/07/01; 1836th graduate of the United States Military Academy; Brevet 2d Lieutenant, 2d Dragoons, 1859/07/01; 2d Lieutenant, 1st Dragoons, 1860/02/28; 1st Lieutenant, 1861/05/07; Captain, 1862/01/16; Brevet Major, 1862/05/05, for gallant and meritorious service in the Battle of Williamsburg, Virginia; Brevet Lieutenant Colonel, 1864/09/19, for gallant and meritorious service in the Battle of Winchester, Virginia; Brevet Colonel, 1868/12/01, for zeal and energy while in command of troops operating against hostile Indians in 1866, 1867 and 1868 – Major, 2d Cavalry, 1869/04/08.”

It’s enough – Henderson’s article is worth reading.

Leave a comment