Medscape ran an article titled “BMI Is a Flawed Measure of Obesity. What Are Alternatives?” The argument ran:

“BMI is also inherently limited by being “a proxy for adiposity” and not a direct measure, added Wee, who is also director of the Obesity Research Program of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts.

As such, BMI can’t distinguish between fat and muscle because it relies on weight only to gauge adiposity, noted Tiffany Powell-Wiley, MD, an obesity researcher at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Maryland. Another shortcoming of BMI is that it “is good for distinguishing population-level risk for cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases, but it does not help as much for distinguishing risk at an individual level,” she said in an interview.”

That is probably as factual as a complaint can be – but the thing is, Quetelet didn’t develop the equation for the purposes of modern medicine. His goal was an equation that would allow measurements of height and weight to be normalized – a number that would show the normal proportions instead of being skewed by height. The medical folks just grabbed his equation because it was easy to use.

Let me take part of his story from the Britannica – “Belgian mathematician, astronomer, statistician, and sociologist known for his application of statistics and probability theory to social phenomena.”

Adolphe Quetelet is one of ours – an example of the many fields that converge to make an insightful demographer. He developed his equation – it was first known as “Quetelet’s Index” as part of his studies on the average man.

This article, Adolphe Quetelet and the Evolution of Body Mass Index (BMI) | Psychology Today describe his work – primarily in demography and statistics:

“He established the first international conference on statistics, and some consider him one of the founders of statistics as a scientific discipline. He was most fascinated with regularity in statistical patterns (Desrosières, The Politics of Large Numbers, 1998) and collected data on rates of crime, (with an interest in what he called “moral anatomy”), marriage, mental illness, and mortality, including suicides. (Porter, 1985) He believed that conclusions come from data of large numbers—populations—rather than from a study of individual peculiarities. For Quetelet, perfection in science was related to how much it could rely on calculation. Many of these original ideas are found in his classic A Treatise on Man and the Development of His Faculties . . .”

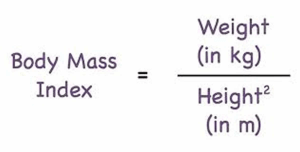

The BMI is criticized because it doesn’t work well at the extremes . . . calculations for short fat people can show respectable Body Mass Indices, while tall muscular folks can slide into the overweight and obese categories. That failure is a question of the time when he developed the equations – the BMI equation is:

It has one exponent – your height is squared. Quetelet, though brilliant, was a generation earlier than the folks who worked with fractional powers. I’ve played with the equation – and changing it from simply squaring the height to raising the height to the 1.9 power greatly reduces the problem at both ends. Quetelet’s main work was in the 1840’s – the concept of fractional powers kicked in a generation later. As an aside, Quetelet would probably have lived his life an a respected Belgian astronomer if not for the revolution that kicked him out of his observatory. Not everyone grows up with plans of being an outstanding social scientist and inventing aspects of demography.

Quetelet’s index isn’t flawed – the problem is that it was repurposed 150 years after he developed it, and it wasn’t updated. The Atlantic has a good article on Quetelet at How the Idea of a ‘Normal’ Person Got Invented – The Atlantic. It’s worth reading. So far as your BMI score goes – it’s not bad when your height begins with 5 feet . . . the problems really show up below 5 feet and above 6 feet.

Leave a comment