By AmberLi Emery

When One Cow Is Regulated Like a Commercial Operation

Montana’s livestock regulations were created with a clear and important purpose: protecting animal health, preventing disease outbreaks, and safeguarding access to agricultural markets. Most producers — large and small — support those goals.

But over time, the way these regulations are applied has drifted away from proportionality. Today, a growing number of homesteaders, hobby farmers, and micro-farm operators are discovering that households with one cow or a few sheep are being treated, administratively, the same as commercial livestock operations.

That reality deserves a closer look.

What’s Actually Happening

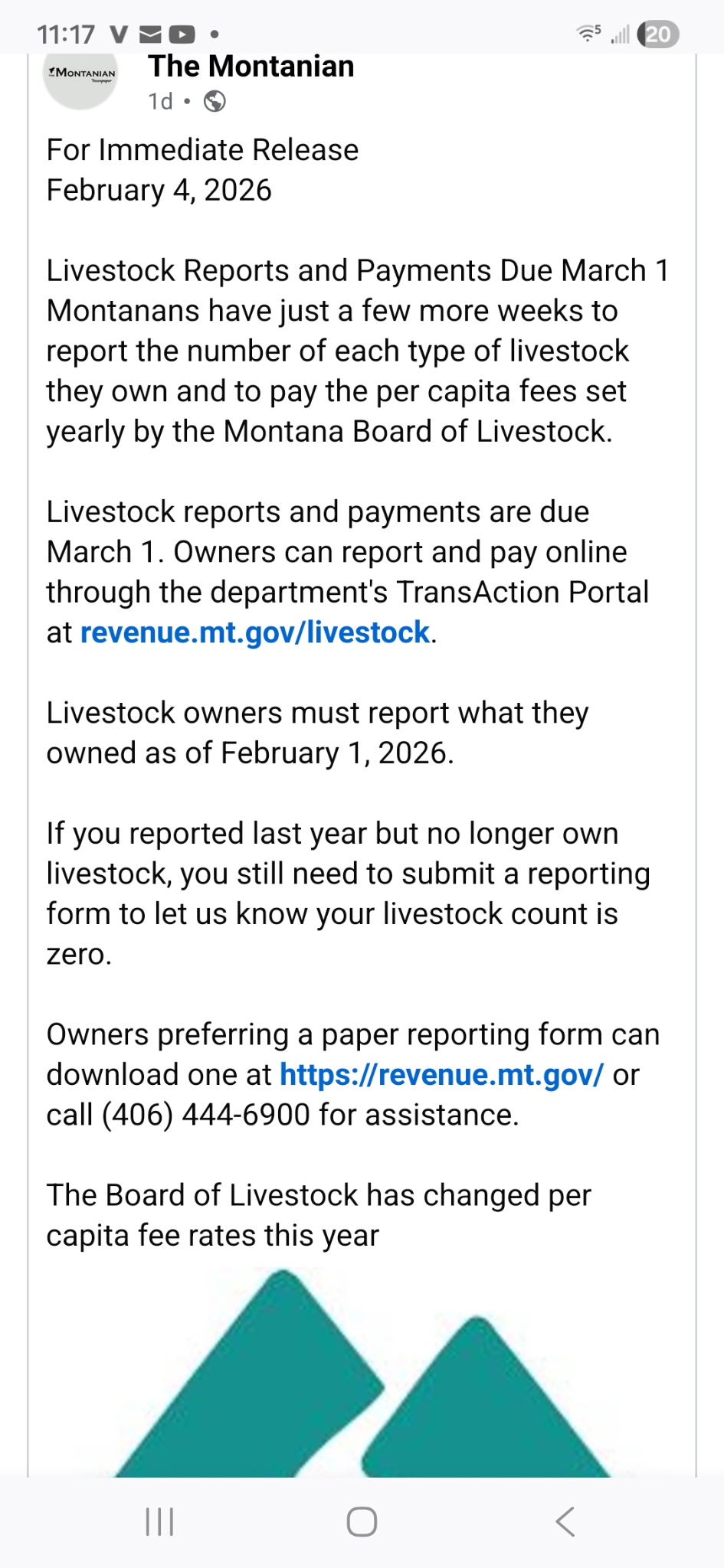

Under current law, livestock owners must file annual reports and pay per-head fees. On paper, the fees themselves are small. For a homestead with one cow and a few sheep, the total may amount to only a few dollars.

The issue is not the dollar amount.

�The issue is the compliance structure attached to it.

Missed paperwork — not disease risk, not animal movement, not commercial sales — can trigger penalties, interest, collection actions, and future complications with livestock-related transactions. In other words, a minor administrative obligation can escalate quickly into a significant burden.

For large commercial operations with staff, accountants, and routine regulatory interaction, this is manageable. For small households raising animals for personal use, food security, or land stewardship, it is not.

Why Scale Matters

Homesteads and micro-farms differ fundamentally from commercial operations:

- They do not move livestock through interstate markets

- They do not sell at scale

- They do not export systemic disease risk

- They are not part of industrial supply chains

Yet they are subject to the same reporting deadlines, the same penalty structures, and the same enforcement tools.

That mismatch doesn’t improve animal health outcomes. What it does do is quietly discourage small-scale livestock ownership through accumulated friction — forms, deadlines, and the risk of penalties disproportionate to the activity being regulated.

This is not a theoretical concern.

Across rural communities, families are choosing to stop keeping animals not because they cannot manage them, but because the regulatory overhead no longer feels worth it.

A Question of Proportional Regulation

This is not an argument against livestock oversight. Disease control, inspection programs, and brand enforcement are essential and widely supported.

The question is whether regulation should reflect scale, intent, and impact.

A household with one cow for family milk and meat does not present the same regulatory risk as a commercial operation moving hundreds of animals through markets. Treating them identically is not precision regulation — it is blunt administration.

Other areas of law routinely recognize thresholds and exemptions for small-scale, non-commercial activity. Livestock regulation can do the same without weakening animal health protections.

What a Balanced Approach Could Look Like

Reasonable reforms might include:

- Exempting minimal, non-commercial livestock ownership from annual reporting and per-capita fees

- Establishing a penalty floor so de minimis obligations do not trigger enforcement actions

- Automatically sunsetting reporting requirements for households that no longer keep animals

- Focusing enforcement resources on operations that actually participate in markets and animal movement

Such changes would preserve the integrity of animal health programs while reducing unnecessary pressure on small producers.

Why This Matters Beyond the Farm Gate

The gradual loss of homesteads and micro-farms has broader implications. Small-scale livestock ownership supports:

- Food independence

- Rural resilience

- Agricultural knowledge passed between generations

- A diversified, less fragile food system

When regulations unintentionally push these households out, the result is greater consolidation — fewer producers, fewer hands in agriculture, and more distance between families and their food.

That outcome was never the intent of Montana’s livestock laws. But intent matters less than impact.

The Conversation We Need to Have

This is not a partisan issue, nor is it a conflict between “big ag” and “small ag.” It is a question of whether regulation keeps pace with reality.

Protecting animal health and supporting self-sufficiency should not be competing goals. With thoughtful, proportional reform, Montana can do both.

The first step is acknowledging that when one cow is regulated like a commercial operation, something in the system has gone off balance.

Leave a comment