I recently started working for the United States Postal Service, and, while I’ve been seeing quite a few bugs lately, few are the kind I like. While I’m not terribly fond of them, the sheer numbers these bugs occur in has been very impressive.

Mercifully, with elections past, there’s been a sizeable reduction in the numbers of incoming bugs in our P.O. boxes.

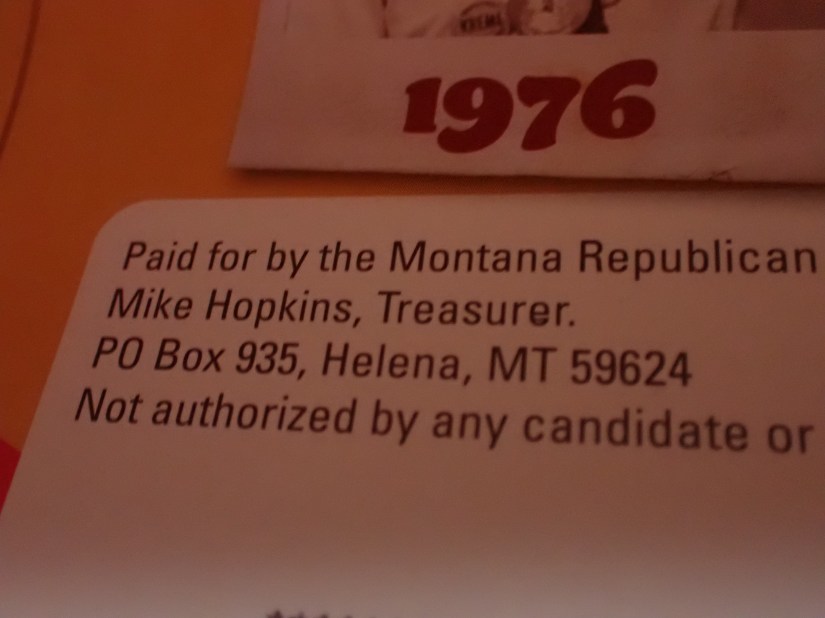

I’m talking about union bugs, specifically printers’ union bugs. These minuscule beasties seem to be on well more than half of our political junk mail this season! Here’s some fine examples of the species:

These strange ink-based critters colonize almost all publications that come out of unionized printing presses.

If you’ll notice, there’s a certain bias in the political affiliation of these bugs. At present, almost all Democrat-leaning political flyers are published in unionized print shops. Republican-leaning political flyers, on the other hand, are seldom published in unionized print shops, and most lack union bugs.

This trend doesn’t necessarily hold constant across the country, though. Nor has it held constant over time – unions used to be strongly supported by the right, as a way that capitalism led to better worker conditions. And, alas, the presence of the union bug is no longer as indicative of an entirely union-made product as it once was…

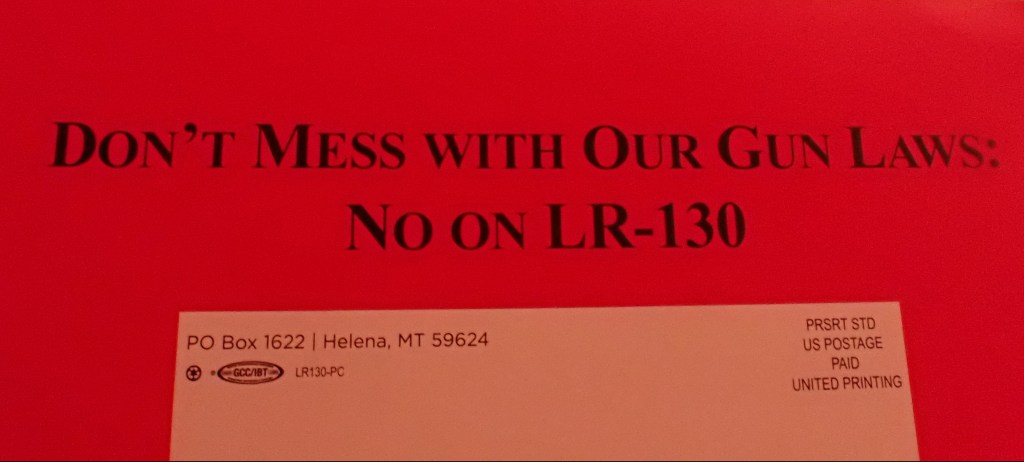

Due to prevalent local political sentiments, certain political flyers have been disguising themselves to sneak their messages into new homes. Take a look at this piece of political mail – at first glance, you’d assume that LR-130 is opposed to the Second Amendment.

But look closer!

A union bug. This indicates a union press was used, and the flyer in question was most likely published by a left-leaning group. When we examine the bones of this legislation, LR-130 is actually in favor of the Second Amendment.

Cleverly camouflaged flyers and a fair bit of funding led to a surprisingly close vote on LR-130. It’s important to be well-informed on what the issues we’re voting on actually are – legislation and flyers rarely aim to be straightforward.

Mercifully, while pests of a sort, political flyers do not reproduce, unlike invasive insects. Personally, I’m rather grateful that we only have to deal with this volume of political propaganda once every four years.