Benjamin L. Emerson, Georgia Institute of Technology

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Why does a rocket have to go 25,000 mph (about 40,000 kilometers per hour) to escape Earth? – Bo H., age 10, Durham, New Hampshire

There’s a reason why a rocket has to go so fast to escape Earth. It’s about gravity – something all of us experience every moment of every day.

Gravity is the force that pulls you toward the ground. And that’s a good thing. Gravity keeps you on Earth; otherwise, you would float away into space.

But gravity also makes it difficult to leave Earth if you’re a rocket heading for space. Escaping our planet’s gravitational pull is hard – not only is gravity strong, but it also extends far away from Earth.

Like a balloon

As a rocket scientist, one of the things I do is teach students how rockets overcome gravity. Here’s how it works:

Essentially, the rocket has to make thrust – that is, create force – by burning propellant to make hot gases. Then it shoots those hot gases out of a nozzle. It’s sort of like blowing up a balloon, letting go of it and watching it fly away as the air rushes out.

More specifically, the rocket propellant consists of both fuel and oxidizer. The fuel is typically something flammable, usually hydrogen, methane or kerosene. The oxidizer is usually liquid oxygen, which reacts with the fuel and allows it to burn.

When going into space and escaping from Earth, rockets need lots of force, so they consume propellant very quickly. That’s a problem, because the rocket can’t carry enough propellant to keep thrusting forever; the amount of propellant needed would make the rocket too heavy to get off the ground.

So what happens when the propellant runs out? The thrust stops, and gravity slows the rocket down until it gradually begins to fall back to Earth.

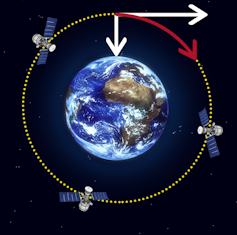

Fortunately, scientists can launch the rocket with some sideways momentum so that it misses the Earth when it returns. They can even do this so it continuously falls around the Earth forever. In other words, it goes into orbit, and begins to circle the planet.

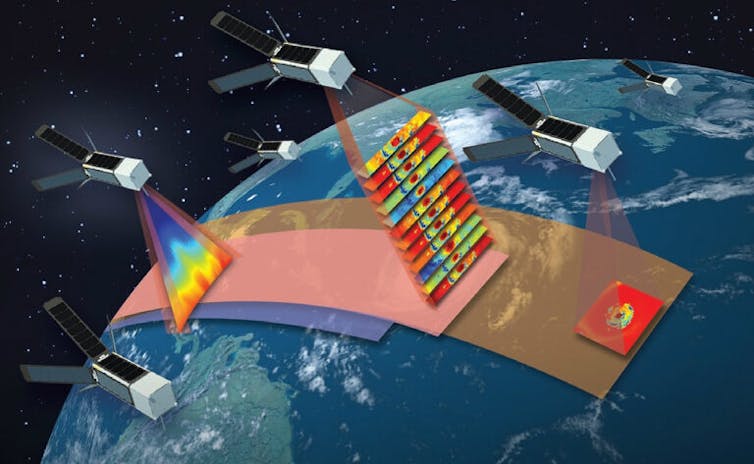

Many launches intentionally don’t completely leave Earth behind. Thousands of satellites are orbiting our planet right now, and they help phones and TVs work, display weather patterns for meteorologists, and even let you use a credit card to pay for things at the store or gas at the pump. You can sometimes see these satellites in the night sky, including the International Space Station.

Escaping Earth

But suppose the goal is to let the rocket escape from Earth’s gravity forever so it can fly off into the depths of space. That’s when scientists do a neat trick called staging. They launch with a big rocket, and then, once in space, discard it to use a smaller rocket. That way, the journey can continue without the weight of the bigger rocket, and less propellant is needed.

But even staging is not enough; eventually the rocket will run out of propellant. But if the rocket goes fast enough, it can run out of propellant and still continue to coast away from Earth forever, without gravity pulling it back. It’s like riding a bike: build up enough speed and eventually you can coast up a hill without pedaling.

And just like there’s a minimum speed required to coast the bike, there’s a minimum speed a rocket needs to coast away into space: 25,020 mph (about 40,000 kilometers per hour).

Scientists call that speed the escape velocity. A rocket needs to go that fast so that the momentum propelling it away from Earth is stronger than the force of gravity pulling it back. Any slower, and you’ll go into an orbit of Earth.

Escaping Jupiter

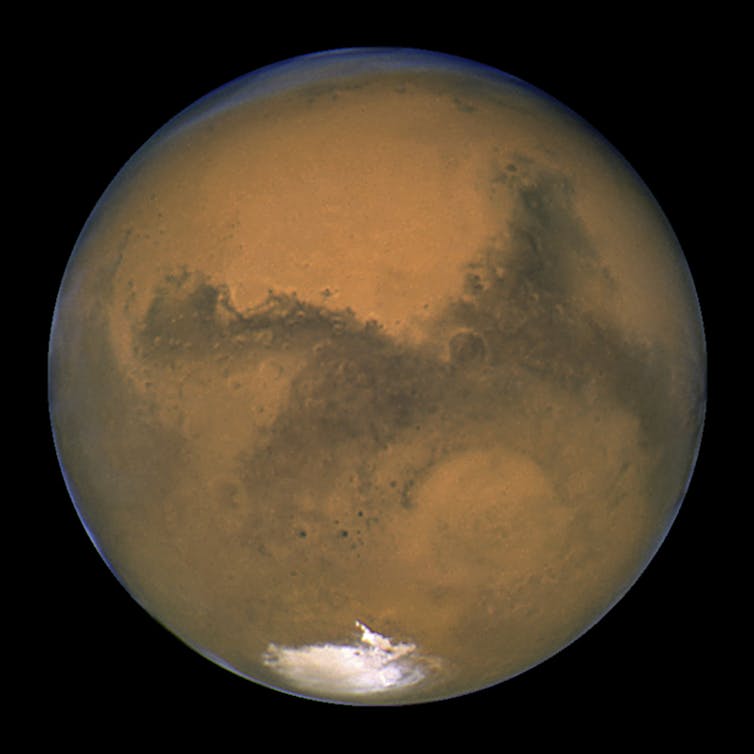

Bigger, or more massive, objects have stronger gravitational pull. A rocket launching from a planet bigger than Earth would need to achieve a higher escape speed.

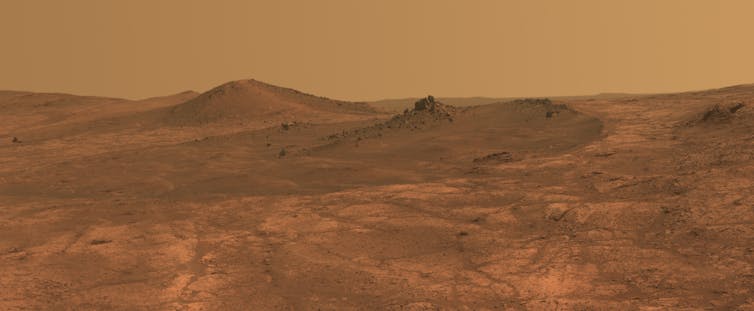

For example, Jupiter is the most massive planet in our solar system. It’s so big, it could swallow 1,000 Earths. So it requires a very high escape speed: 133,100 mph (about 214,000 kilometers per hour), more than five times the escape speed of Earth.

But the extreme example is a black hole, an object so massive that its escape speed is extraordinarily high. So high, in fact, that even light – which has a speed of 370 million mph (about 600 million kilometers per hour) – is not fast enough to escape. That’s why it’s called a black hole.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

Benjamin L. Emerson, Principal Research Engineer, School of Aerospace Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.