I watched a video of a 9mm being fired into a pond’s ice surface, and the bullet spinning like a top. It’s an experiment that I don’t plan to duplicate, since my feet have enough problems without doing something dumb – but the video does lead in to an explanation of rifling. The gun handling is not exemplary – but the results are worth watching.

I am not an expert on firearms – but during the middle of the 1980’s, I was tasked with developing a class that brought gunsmithing students toward computer literacy. It was a time when personal computers and I were young – and the work assignment gave me a great learning opportunity, as well as teaching.

It’s common knowledge that rifling – the twisting grooves inside the barrel – cause the bullet to spin, and that spinning the bullet increases accuracy. If you take that knowledge, and go to the tables that show rate of twist for rifling in specific calibers, and couple that with the tables on muzzle velocity, you can come up with some absolutely fascinating numbers. Rifling Twist Rate is a good article by Chuck Hawks on the topic.

One of the problems I shared with my students was determining how many revolutions per minute the bullet from my 1903A3 Springfield was making, when I fired a 30/06 accelerator. This required the students to find the muzzle velocity of the cartridge (listed at 4,000 feet per second, and the rate of twist in the Springfield (1 turn in 10 inches – and not ideal for match use).

If you’re willing to look at RPM at the muzzle, the math is straightforward – one turn in ten inches is 1.2 turn in a foot – so, as the bullet leaves the muzzle, it’s spinning 4800 revolutions per second. Multiply that by 60 seconds in a minute and you’re left with a 55 grain bullet spinning at 288,000 RPM.

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to realize that something spinning that fast really wants to come apart. It’s part of the reason ammunition manufacturers make different types of bullets – not everything is expansion. During the War Between The States, the rate of twist for rifled muskets was somewhere between one turn in 48 inches and one turn in 72 inches – which provided pretty good accuracy for those 58 caliber beasts. Muzzle velocity was around 900 feet per second – which, with a 72 inch twist gives 150 turns per second, or 9,000 RPM. The spin was slow enough that a lead bullet could hold together easily.

Years ago, I spoke with a gun expert who had a 17 Remington – she didn’t like recoil and explained that her rifle substituted speed for bullet weight. It’s another 4000 ft per second rifle – and the twist is 1 turn for 9 inches – 300,000 RPM in a 25 grain hollow point projectile. Since I could do math, and she was certain of her expertise, there was no point in further discussion. If she’s happy, she has a better deer rifle than I (or you, for that matter).

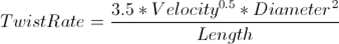

The empirical equation for rifling is (from Hawk):

While we don’t have exact numbers for the bullet in the video, 9mm barrels range between 10” twist and 18 and a fraction. Since I’m ballparking, let’s assume 12” twist and a muzzle velocity of 1,000 feet per second. The bullet would have hit the ice spinning at 60,000 rpm. Small wonder that it spun like a top – but I won’t duplicate the experiment, and I recommend no one else does either.