When I listened to the explanations that the California and Oregon fires were worse than ever, and resulted from anthropic climate change, I did what I usually do. I checked for data and found statistics at the National Interagency Fire Center.

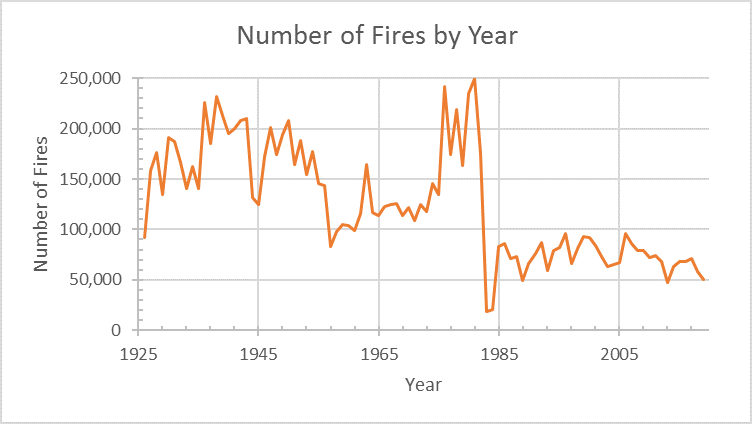

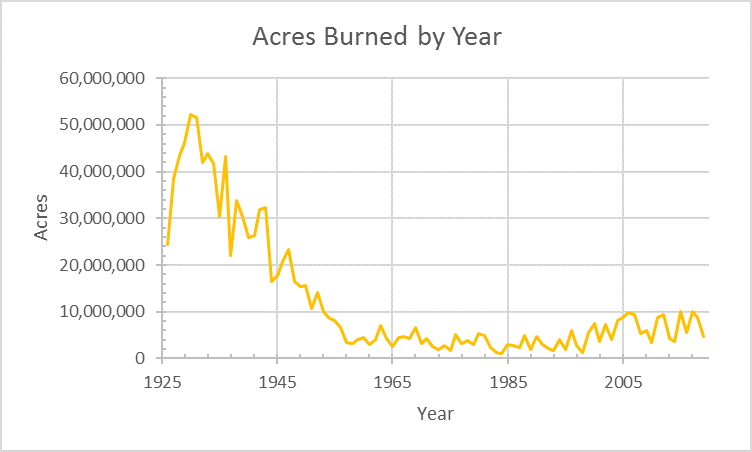

The table I found lists both number of fires, and acreage burned by year, starting in 1926. That’s almost a hundred years, and a lot of numbers. Since graphs tend to easier to read, line graphs follow. The drop in number of fires in 1984 is a dramatic shift, The drop in acreage burned that occurred in the fifties is an equally dramatic shift.

Both sets of data are partial duration series – and a significant part of my life has been making projections from partial duration series, and teaching how to do it. Not predicting the future, you understand just projecting the data. It would have been nice to have this data for the classroom – you can see how taking either the left half of the graph, or the center half, or the right half, and projecting a line through it, would lead to very different projections.

Our largest years for fires were pretty much between 1926 and 1952. I had remembered 1988 as particularly bad – but the statistics show that it was perspective – Yellowstone Park burned, then at the end of the year, Dry Fork was almost in the backyard. Five million acres burned is a lot – but compared to 52 million in 1930, it seems small. Memory is influenced by perspective, and my memory of the 1988 fire season was “Montana-centric.”

The graphs look very different if you cut the data down to just 20 years. Most of the time, our data is a partial duration series. Tweaking reality from a partial duration series isn’t always easy – and the past century’s forest fire data shows the challenges. The projection can’t be better than the data.