-

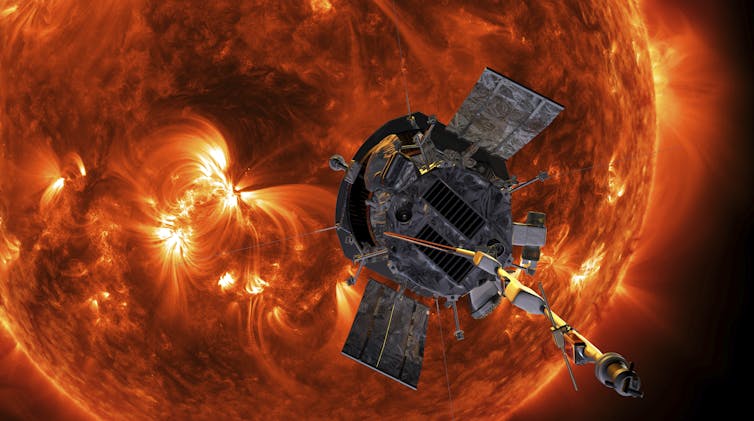

This artist’s rendition shows NASA’s Parker Solar Probe approaching the Sun. Steve Gribben/Johns Hopkins APL/NASA via AP Yeimy J. Rivera, Smithsonian Institution; Michael L. Stevens, Smithsonian Institution, and Samuel Badman, Smithsonian Institution

Our Sun drives a constant outward flow of plasma, or ionized gas, called the solar wind, which envelops our solar system. Outside of Earth’s protective magnetosphere, the fastest solar wind rushes by at speeds of over 310 miles (500 kilometers) per second. But researchers haven’t been able to figure out how the wind gets enough energy to achieve that speed – until now.

Our team of heliophysicists published a paper in August 2024 that points to a new source of energy propelling the solar wind.

Solar wind discovery

Physicist Eugene Parker predicted the solar wind’s existence in 1958. The Mariner spacecraft, headed to Venus, would confirm its existence in 1962.

Since the 1940s, studies had shown that the Sun’s corona, or solar atmosphere, could heat up to very high temperatures – over 2 million degrees Fahrenheit (or more than 1 million degrees Celsius).

Parker’s work suggested that this extreme temperature could create an outward thermal pressure strong enough to overcome gravity and cause the outer layer of the Sun’s atmosphere to escape.

Gaps in solar wind science quickly arose, however, as researchers took more and more detailed measurements of the solar wind near Earth. In particular, they found two problems with the fastest portion of the solar wind.

For one, the solar wind continued to heat up after leaving the hot corona without explanation. And even with this added heat, the fastest wind still didn’t have enough energy for scientists to explain how it was able to accelerate to such high speeds.

Both these observations meant that some extra energy source had to exist beyond Parker’s models.

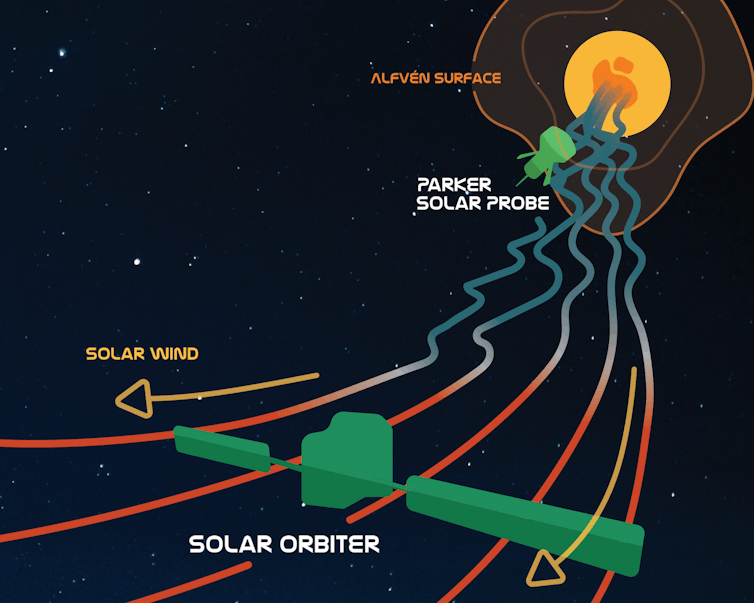

This artist’s rendition shows the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter orbiting the Sun. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab Alfvén waves

The Sun and its solar wind are plasmas. Plasmas are like gases, but all the particles in plasmas have a charge and respond to magnetic fields.

Similar to how sound waves travel through the air and transport energy on Earth, plasmas have what are called Alfvén waves moving through them. For decades, Alfvén waves had been predicted to affect the solar wind’s dynamics and play an important role in transporting energy in the solar wind.

However, scientists couldn’t tell whether these waves were actually interacting with the solar wind directly or if they generated enough energy to power it. To answer these questions, they’d have to measure the solar wind very close to the Sun.

In 2018 and 2020, NASA and the European Space Agency launched their respective flagship missions: the Parker Solar Probe and the Solar Orbiter. Both missions carried the right instruments to measure Alfvén waves near the Sun.

The Solar Orbiter ventures between 1 astronomical unit, where the Earth is, and 0.3 astronomical units, a little closer to the Sun than Mercury. The Parker Solar Probe dives much deeper. It gets as close as five solar diameters from the Sun, within the outer edges of the corona. Each solar diameter is about 865,000 miles (1,400,000 kilometers).

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe and ESA’s Solar Orbiter missions measured the same stream of plasma flowing away from the Sun at different distances. Parker measured lots of magnetic waves near the edge of the corona – called the Alfvén surface – while Solar Orbiter, located past the orbit of Venus, observed that the waves had disappeared and that their energy had been used to heat and accelerate the plasma. Arya De Francesco With both these missions operating together, not only can researchers like us examine the solar wind close to the Sun, but we can also study how it changes between the point where Parker sees it and the point where the Solar Orbiter sees it.

Magnetic switchbacks

In Parker’s first close approach to the Sun, it observed that the solar wind near the Sun was indeed abundant with Alfvén waves.

Scientists used Parker to measure the solar wind’s magnetic field. At some points they noticed the field lines – or lines of magnetic force – waved at such high amplitudes that they briefly reversed direction. Scientists called these phenomena magnetic switchbacks. With Parker, they observed these energy-containing plasma fluctuations everywhere in the near-Sun solar wind. https://www.youtube.com/embed/plabpsKpydE?wmode=transparent&start=0 Magnetic switchbacks are brief reversals in the solar wind’s magnetic field.

Our research team wanted to figure out whether these switchbacks contained enough power to accelerate and heat the solar wind as it traveled away from the Sun. We also wanted to examine how the solar wind changed as these switchbacks gave up their energy. That would help us determine whether the switchbacks’ energy was going into heating the wind, accelerating it or both.

To answer these questions, we identified a unique spacecraft configuration where both spacecraft crossed the same portion of solar wind, but at different distances from the Sun.

The switchbacks’ secret

Parker, close to the Sun, observed that about 10% of the solar wind energy was residing in magnetic switchbacks, while Solar Orbiter measured it as less than 1%. This difference means that between Parker and the Solar Orbiter, this wave energy was transferred to other energy forms.

We performed some modeling, much like Eugene Parker had. We built off modern implementations of Parker’s original models and incorporated the influence of the observed wave energy to these original equations.

By comparing both datasets and the models, we could see specifically that this energy contributed to both acceleration and heating. We knew it contributed to acceleration because the wind was faster at Solar Orbiter than Parker. And we knew it contributed to heating, as the wind was hotter at Solar Orbiter than it would have been if the waves weren’t present.

These measurements told us that the energy from the switchbacks was both necessary and sufficient to explain the solar wind’s evolution as it travels away from the Sun.

Not only does our measurement tell scientists about the physics of the solar wind and how the Sun can affect the Earth, but it also may have implications throughout the universe.

Many other stars have stellar winds that carry their material out into space. Understanding the physics of our local star’s solar wind also helps us understand stellar wind in other systems. Learning about stellar wind could tell researchers more about the habitability of exoplanets.

Yeimy J. Rivera, Researcher in Astrophysics, Smithsonian Institution; Michael L. Stevens, Researcher in Astrophysics, Smithsonian Institution, and Samuel Badman, Researcher in Astrophysics, Smithsonian Institution

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

-

A drive to Kalispell shows the narrow passage between stream and stone as you travel past the Point of Rocks – a term that preceded the restaurant that burned several years ago. You can note it as you drive between Eureka and Olney – a place where the rock wall almost pushed the early travelers into the Stillwater River. The first ten years of the 20th Century opened travel to Trego – partially with the railroad pushing a line through from Whitefish to Eureka, where it joined the routes down the Kootenai River from Canada.

For Trego, commercial transportation began with the Splash Dam on Fortine Creek – built around 1905, and last used in 1954. The remains of the dam are about a mile south of Trego School, on the Dickinson place. This photo, from 1922, gives an idea of Trego’s early history. (Note the logs along the bank, waiting for the next flood to transport them to the mill in Eureka)

I recall my grandmother’s concerns about playing by the creek – and hadn’t realized that the final use of floods to transport the logs occurred when I was four or five years old. And that memory brought the message home that most folks who live here don’t know just how important the dam was in settling Trego.

A dozen years after the dam was built, Trego became the site of labor unrest. ‘Big Daddy’ Howe ran the lumber company in Eureka, and the laborers who ran the logs down Fortine Creek and the Tobacco River were unionizing – chief among their demands was a call for hot showers as part of the working requirements.

Waseles was known as Mike Smith – and ran the crew that specialized in the twenty-mile river run that kept the mill running in Eureka. He died without any known next-of-kin, so P.V. Klinke (assigned as executor by the county) sold his homestead (just below the dam) and bought the large tombstone you see as you drive into Fortine Cemetery. Their 1917 strike grew into a nationwide timber strike, and Howe developed a hatred of organized labor . . . specifically the International Workers of the World, the IWW.

When Waseles died, he was under indictment for torching a logging camp, and for sabotaging the log runs by throwing all the tools he could into the pond behind the dam.

Trego was typecast as a hotbed of socialist wobblies for many years by Eureka’s elites – a view that diminished rapidly with the many union jobs that came into both communities with the railroad relocation that accompanied Libby Dam in the sixties.

By Loco Steve, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=54585133 The logging dam operated for about a half-century, and was mostly gone by the time the railroad mainline bypassed both Trego and Eureka – but the sounds of the trains still are heard in Trego in the 21st Century. And the Jake Brakes of logging trucks have replaced the floods that moved the logs down Fortine Creek to the sawmills.

-

by Donna Kallner, The Daily Yonder

August 23, 2024Affordable rural housing stock is almost as scarce as large animal veterinarians these days. We happen to know one of that rare breed (we call her the Cow Whisperer), and she recently found a house to buy. The price was reasonable for a starter home because it needs some work. It’s not a “Let’s restore a Victorian painted lady” fixer upper, but it needs more than a fresh coat of paint. She knows what to expect.

But if you’ve lived in or tried to renovate an old farmhouse, you can understand the temptation to put a match to it and walk away. There’s a point at which it seems pointless to continue battling mice, jerry-rigged plumbing, and bird and rodent nests near wiring that wouldn’t pass any building code inspection. The shed snake skin I found nestled among my canning jars drove me closer to arson than any of our many domestic encounters with bats.

When we were younger, visitors knew to prepare for nights in our unheated, uninsulated upstairs bedrooms like a winter camping adventure. It’s just the way it was. Then I was in a serious motor vehicle accident. Maneuvering on crutches was hard enough. But the dark, narrow passage from the kitchen to the miniscule bathroom (better than an outhouse but not much)? That really tested my mettle. And that’s after my husband duct-taped open the accordion door so I didn’t have to wrestle it open and closed.

It became clear that aging in place would require big changes. So we did the math on what it would cost to rewire, insulate, and build an addition for a bath/laundry/kitchen that could be plumbed without venting the soil pipe through a kitchen cupboard. The cost was enough that it made more sense to choose new construction on the same property.

But that left us with the question of what to do about the old house – or as my husband called it, the one that was paid for. We had no interest in dividing the property to sell part, or in renting out the house: Either would have required difficult and costly choices about our well, septic system and electrical service. We didn’t know anyone willing to take on the expense of moving a structure that would need so much work. Or anyone willing to dismantle it and haul away everything, not just the limited materials that could be reused. Letting it stand wasn’t an option for tax, insurance and other reasons: Empty structures can attract meth cookers and people who strip out copper and other materials, and we could still be liable if anyone was injured on our property.

In the end, we did burn it – as a training exercise for local volunteer fire departments. But a lot went into the preparation for that controlled burn in May of 2002.

As a member of my local volunteer fire department, I’ve been on a number of calls where building materials were intentionally burned without that control. In some cases, the responsible party was genuinely surprised that anyone would call 911, and that people can’t just burn or bury anything they want to on their own property in the country. After all, that was a common practice at one time, so they may have known people who did just that and got away with it. But nowadays it takes an Oscar-caliber performance to achieve forgiveness when you didn’t first get permission to burn or bury demolition waste.

That’s because there are health and safety risks associated with disposal of construction and demolition (C&D) materials, and state laws that regulate their disposal. In Wisconsin, you can face fines and penalties if you burn a structure or if there is documented environmental damage caused by waste disposed of on your land. And you may be held liable for environmental cleanup. Burying C&D waste on your land could significantly reduce your property value and make you liable to future landowners. Reduced property value or fulfilling the contingency requirements for cleanup could cost more than simply managing the waste properly to begin with.

For the controlled burn of our old farmhouse in 2002, the first step was a conversation with our volunteer fire chief. He directed us to the Department of Natural Resources for guidelines on our responsibilities.

We had to have a state-certified inspector come out to examine the structure. He took samples of shingles, siding and ceiling materials, and examined the interior for flooring that might have contained asbestos. Lab results indicated no asbestos, so we were not required to do asbestos abatement. We received a letter attesting to inspection results to give to our fire chief so he could proceed with planning for the burn.

We did not have to remove asphalt shingles, which is required “unless they are considered necessary to the fire practice” (roof venting was one of the training evolutions). We did have to remove furniture, appliances and household items, even if we hadn’t needed them in the new house. I think many people don’t know how much toxic smoke and gas can be released by burning the foams, plastics, adhesives and petroleum products in furnishings.

Our fire chief developed plans for the training and the demolition burn. We identified hazards like the creepy open cistern in the basement. Advance preparations included nailing sheets of OSB over upstairs windows to help minimize airflow during training exercises. We also covered the large picture windows downstairs to help manage flames and heat radiating toward other exposures during the burn.

In a rural area like ours, there are no nearby fire hydrants, so water is often moved to the scene by what is called a tender relay. On the day of the burn, our local volunteer fire department was joined by several neighboring departments to participate in the training exercises and to assist with the burn. They set up a portable pump in the river by the fire station, less than two miles away, and used three tenders to move water from that fill site to our location.

First up that day was a roof venting training exercise. Firefighters worked from a roof ladder hooked to the peak, using a specialized saw to cut through roofing materials and rafters.

The plan was to start the controlled burn in the single-story kitchen addition. Once that burned, the two-story main structure could collapse toward that and away from the new house. (Photo by Donna Kallner) The other training evolutions were conducted in upstairs bedrooms. As is true in many old farmhouses, the stairs to those bedrooms were steep and narrow, with irregular step heights and tread depths. Imagine navigating those in full bunker gear, breathing apparatus and face shields while managing a firehouse pressurized from the engine and ready to deliver water to a fire. Now imagine doing that with smoke filling the space.

After putting out several training fires upstairs, the chief called a break for volunteers to eat the lunch my mom and I had prepared for them. During that time, the wind started to pick up. The chief elected to cut a final planned training evolution and conduct the burn before the wind could increase or shift toward our new house.

Even though you’re not trying to put out a structure fire, it takes a lot of firefighters for a controlled burn. There were firefighters working a hose line to cool the siding on the new house so it wouldn’t be damaged. They set up water curtains to protect our liquid propane tank and another small structure. There was an engine operator pumping water, another on a backup engine, and a fill site boss working with the tender relay drivers. We shouldhave had a few more people on the highway to manage traffic before every Looky-Lou passerby pulled off on the shoulder to watch the fire, thereby blocking access to the driveway for those tender drivers so that we almost ran out of water.

The chief had a plan to burn the old house starting with the single-story kitchen addition on the far side away from the new house. Once that burned, the two-story main structure could collapse toward that and away from our new house. And that’s exactly what happened. Eventually. While I was quietly freaking out at how quickly our bedroom was fully engulfed in flame, others were marveling at how long it took for the walls and central chimney to come down.

And that’s not all. Without suppression measures, the fire got so hot it melted the glass in those picture windows. There were a couple of floor joists that didn’t burn. But with so much heat and so much air, there was little left by the time the fire was done.

Before that, things got a little exciting when embers from the structure ignited and started a grass fire. Firefighters fought that and kept a minor crown fire in a red pine tree from blowing up. By the end of that day, I was grateful beyond measure to every one of the volunteers who contributed to a successful training and to a successful demolition burn.

Our fire department regularly gets inquiries from people interested in donating a structure for a training burn. Sometimes we don’t hear from them again after they learn it’s not as simple as just tossing a match. But when we do, we get valuable live fire training and a chance to help our community remove a structure that has outlived its usefulness.

Donna Kallner writes from Langlade County in rural northern Wisconsin.

This article first appeared on The Daily Yonder and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

-

Thinking of my many political choices, I remembered the ninth beatitude – the one that can’t be found in the bible: “Blessed are they who expect nothing, for they shall not know disappointment.” I decided to look up the phrase, and found that the first author credited with it was Alexander Pope. I also found that I didn’t have the quotation quite right – which is normal operating procedure. Somehow a lot of quotations improve in my memory.

It fits well with politics – when you expect nothing from a politician, he/she cannot disappoint you. Unfortunately, I continue to vote for a candidate that at least offers a possibility of voting for my interests – so I continue to know disappointment.

I’ve been disappointed by my State Senator and my State Representative – both of whom voted to make Trego taxpayers pay tuition for students who choose to attend school in nearby districts. It wouldn’t be unfair – except the lion’s share of our school taxes go to Helena, where a small portion is parsed back to the district to make for equalization. The taxes we send to Helena follow the students as the state sends those dollars to the varying school districts based on a formula involving ANB – average number belonging.

So the state taxes all landowners for education, puts the money in a pot, then doles the money out to school districts based on their enrollment. That was assessed at 77.9 mills last time around, with a second round of taxes at 17.1 mills to make up for the commissioners not taxing enough. It’s listed as the state school levy, and is the largest single levy on the tax bill at 95 mills.

The levy that the local district keeps is the Elementary General Levy – last time around it was 31.97 mills – roughly a third of the State School Levy. Now that levy is assessed tuition for students who go to school outside their home district.

So we’re going to have to take the tuition out of the Elementary General Levy. First we’ve been taxed 95 mills for equalization, and the portion the schools get from those funds is assessed based on students attending – whether the students attend in their home district or not. This year, Trego’s school board will be looking at raising the Elementary General Levy by somewhere on the order of ten percent to cover the tuition to Whitefish and Eureka.

So I am disappointed in Mike Cuffe and Neil Durum. I suspect they just voted party-line on something that they unquestioningly accepted as a good idea – without bothering to ask folks on Trego’s school board what this would do to their community. Blessed are those who expect nothing, for they shall not know disappointment.

Thank heaven Neil has a Democrat opponent this fall. He may have been part of a large group who will be forcing me to vote to raise taxes on my neighbors – but I will vote responsibly this November and mark the box that isn’t associated with his name. Politicians who vote to shaft their constituents should not expect a second vote.

-

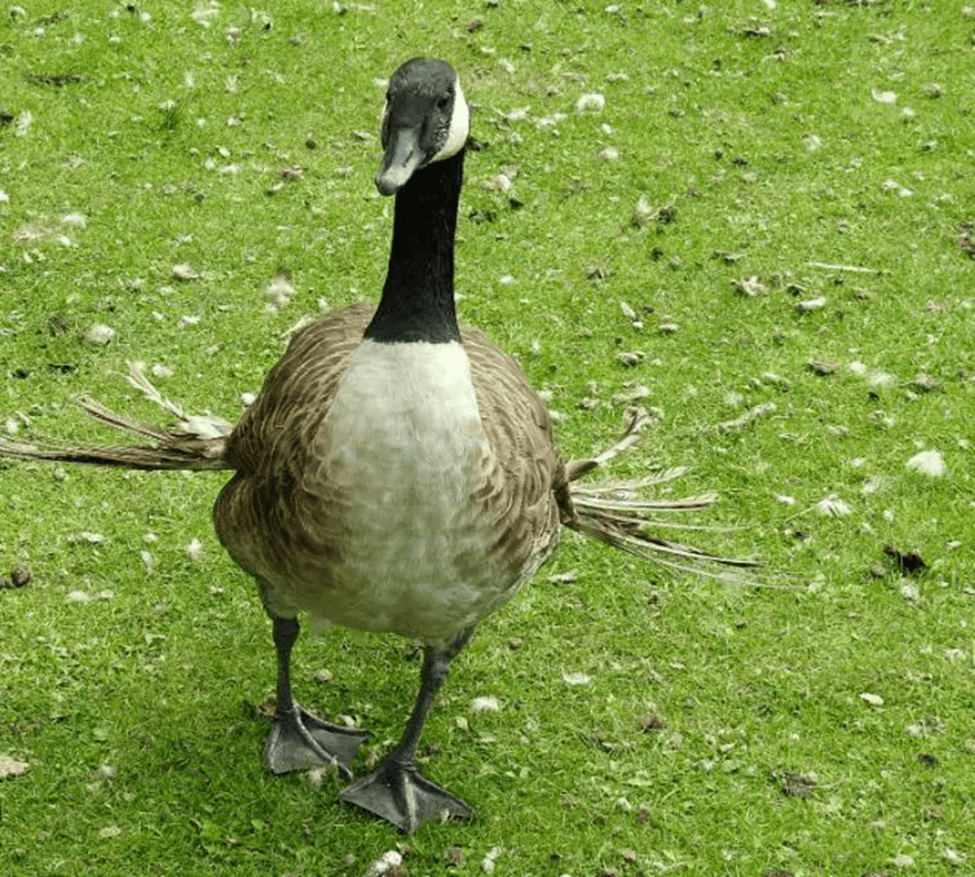

As the last hatch of goslings began their flight training, we noticed that two are being left behind. A bit more observation showed that one is a bit older than the other, but both show enough wing problems in the last joint to qualify them as angel wing. The Poultry Feed provides a description of the condition: “Angel Wing, also known as slipped wing or carpal deformity, is a wing condition that affects the flight feathers of geese. The condition is characterized by the outward twisting or “S” shape of the last joint of the wing, making the feathers point away from the body. This results in an inability for the goose to fold its wings properly, affecting its flight capabilities.”

The site includes this photo, which may be worth the proverbial thousand words in describing the condition:

The two young geese on our pond aren’t nearly so extreme – but a goose who can barely fly is a goose who has to be left behind in the Fall. I’ve been impressed with how long the parents work to try get that last goose airborne, but the end is always the same – the family flies south, and the goose with the wing deformity is left on the same pond where it hatched.

It’s been several years since we encountered the first case of Angel Wing on the pond – the goose could almost fly, and worked hard at it. I kept an aerator on through the winter to keep a bit of open water, and the crippled goose almost made it to Spring – when the Golden Eagle got it. Last year, one with a crippled wing just stayed in the field – easy prey for the Bald Eagle. A goose that can’t fly has problems, and a solitary goose has more problems. This time we’re seeing two crippled geese as Fall approaches. I prefer a world where no goose is left behind – but that isn’t going to be the case this Fall. So I’ll keep an aerator on as Winter sets in – a goose on the water isn’t a real safe target for the eagle. I’ll stick a couple of bales of hay close to the open water – and I’ll feel a bit of sadness when the eagle does harvest the cripple. I’ve never had a pair of crippled geese left behind – in some ways it seems kinder, since a goose without a flock seems pathetically lonesome

-

-

TFS Community Hall News

The land exchange proposed in July has been withdrawn by landowner Mark Kok. The proposal included the TFS Community Hall board granting a 30-foot easement to Kok in exchange for a .8 acre parcel of land north of the TFS Community Hall. Previously, the TFS Community Hall board has sought to buy the land north of the hall to expand the TFS Community Hall’s kitchen and bathrooms.

The hall board is moving forward to develop plans to renovate the kitchen and make the bathrooms ADA compliant without a building expansion.

Trego Heritage Days

The TFS Community Hall board is sponsoring Trego Heritage Days as THE major fund raiser for the TFS Community Hall. The goal is to raise $10,000 to cover a year of the hall’s expenses. Part of the money has been raised through sponsorships. The remainer of the funding will be raised by selling parking passes and music tickets. Parking passes are available at thehalltfs.com website for $10 per car. Music tickets and parking passes will be available the day of the event. Music tickets are separate from parking passes and are $10 per person with children 12 and under free. The goal is to sell over 500 parking passes and/or music tickets. Much of the promotional advertising is occurring in the Flathead valley.

The majority of the heritage events occur Saturday, September 7th. The TFS fireman’s breakfast is Sunday at the hall. On Saturday, a parking pass is required to park on the grounds adjacent to the hall (Mee field) or at Blarney Ranch. There will be food vendors, a beer garden, talks about local history, and music at the TFS community hall. Music is expected to start at 2:30 and continue to 8 pm.

The Trego pub is hosting educations and local agencies information booths as well as fiber demostrations and a MLA logging simulator. Around noon Two Bears Rescue Helicopter is expected to land at the Trego pub. Much of the day’s activities will be at Blarney Ranch including “Coffe with Cows”. Blarney Ranch is hosting ranching, logging, and farming demonstations. There will be a petting zoo (from Poverty Flats), a bouncy house, 3 legged races, sack races, and a pie eating contest for the kids. The ranch will have a vendor village (with local artists), food trucks and beer garden.

Volunteers for the event will receive free parking passes and tickets for the music event. Parking passes will be given out to food bank recipients before the event. With the large crowd expected, come early.

-

by Olivia Weeks, The Daily Yonder

April 5, 2024Editor’s Note: This interview first appeared in Path Finders, an email newsletter from the Daily Yonder. Each week, Path Finders features a Q&A with a rural thinker, creator, or doer. Like what you see here? You can join the mailing list at the bottom of this article and receive more conversations like this in your inbox each week.

New research from American University and the Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund says the currently stalled farm bill is an avenue for reversing historic discrimination against farmers of color by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

I spoke with Sara Clarke Kaplan, executive director of American’s Antiracist Research and Policy Center, to learn more about their new toolkit – “Pointing the Farm Bill Toward Racial Justice.”

Enjoy our conversation about the current state of the farm bill, and Kaplan’s hopes for its future, below.

Black farmers gather at Farm Aid 1999. (Photo courtesy of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund)

What’s the current state of the farm bill? Or, in other words, what’s the occasion for this toolkit?

The farm bill is reauthorized every five years; reauthorization is always a big deal because there’s a tremendous amount of money involved for issues ranging from sustainable agriculture to farm extension programs to nutritional assistance programs. This reauthorization was especially high stakes because of the infusion of money from the Inflation Reduction Act into conservation programs. In 2023, ARPC, The Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund, UC Berkeley’s Food Institute, and AU’s Center for Environment, Community, and Equity convened a national summit on racial justice and the farm bill when Congress was in the process of deliberating a new Bill. Unfortunately, Congress kicked the farm bill reauthorization into 2024 and we still don’t have a new farm bill. That means that the goal of building in policy changes that would increase racial justice is still a critical issue right now.

That said, this work – and this toolkit – isn’t just about a single reauthorization: it’s part of a longstanding and ongoing collaboration of grassroots agricultural organizations and food justice scholars that has produced a strong, lasting coalition of farmers, advocates, researchers, and workers who are seeking to infuse questions of racial equity into food, climate, and agricultural justice. The toolkit reflects that coalitional thinking, with the goal of carrying it forward into ongoing efforts for this eventual farm bill reauthorization and beyond.

Why is the farm bill a good target for justice-oriented demands?

It’s important to remember that the farm bill is a huge omnibus bill, and the primary Congressional vehicle for setting U.S. agricultural and food policy. As such, it’s an instrument for distributing huge amounts of money and for setting multi-year political priorities. It’s not just farm subsidies, it’s the provision of rural broadband, the mediation of food insecurity, the decision of who has access to the treasury of germplasm. These funds are already slated to be spent on agriculture, so the question becomes where these resources will go? How can we ensure that the farm bill’s policies and allocation of resources address the needs, interests, and long term sustainability and wellbeing of all of the diverse people who are impacted by its 12 titles? And if you look carefully, some of the most important racial justice issues of our time are present in the farm bill. Researchers of mass incarceration have traced how when small farmers lose their farms, it opens that land up to prison development; reproductive justice organizers have pointed out that the ability to have and raise children requires secure access to healthy, affordable food; there are so many ways in which the farm bill is a critical site for interventions by people and organizations committed to intersectional racial justice.

This research is based on years of listening sessions and symposia with Black farmers. What were the most surprising findings from those community-based conversations?

Our colleagues at the Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund, conducted two years of extensive listening sessions with their many Black farmer and landowner members in the South. These were led by their former Director of Land Retention and Advocacy, Dãnia Davy, who is now continuing this important work at Oxfam. The results of these unprecedented listening sessions were distilled and presented at the summit, where we continued to discuss them with farmers, researchers, and other allied grassroots organizations. While I can speak to those summit presentations and conversations, our Federation colleagues are really the experts on this.

One point that Federation speakers emphasized was that despite provisions in the previous farm bill for “socially disadvantaged farmers and ranchers” many programs and sources of funding are still not reaching Black farmers. At the summit, we discussed various ideas for making the language in policy more specific about the needs of Black farmers, Indigenous farmers, and other farmers of color.

Our colleagues at the Federation – and Dãnia in particular – also called attention to the intersecting challenges that Black farmers and landowners face that make it even more difficult for them to work the land: lack of broadband internet, the dearth of child and elder care in the communities, etc. It goes without saying that these are issues of racial, social, and economic justice.

Sara Clarke Kaplan is an associate professor of literature and the executive director of American University’s Antiracist Research and Policy Center. (Photo provided by Kaplan) The toolkit’s central tenet is “Climate Justice = Racial Justice = Food Justice = Farm Justice.” Can you elaborate on that idea?

I can imagine that at first glance, this equation might seem cryptic, but it’s crafted to clarify matters by making implicit connections explicit. All too often, discussions of agricultural policy marginalize questions of racial equity and justice, and far too little is known in the broader racial justice movement about the long history and ongoing role that farming and farmers have played in racial liberation struggles in the U.S. and globally. I consider myself as having been part of that problem. I’m relatively new to Farm Justice, with a long history in racial and gender justice movements, but largely in urban settings. Yet the more I learn about central issues in Farm Justice work, the more I see how inextricably these issues and movements are entwined.

Of course, rural participants in grassroots racial justice movements have always known this. Take, for example, projects like Fannie Lou Hamer’s Freedom Farm Cooperative, which enabled Black farmers and sharecroppers who had been excluded, exploited, and terrorized by white landowners to exercise self-determination while providing a source of much-needed food to the hundreds of poor Black families who worked that land. Or take the BIPOC farmers who are innovating new approaches to regenerative agriculture and the building of sustainable, resilient rural communities, who are at the frontlines experiencing the effects of climate change. As long as the vast majority of recent investments in conservation and climate-smart agriculture are directed to white farmers, existing racial disparities will increase, and we will all lose out on opportunities to benefit from the climate-forward work of these small BIPOC farmers.

What’s the connection between American University and this Farm Justice work?

It’s so important to remember the historical relationship between institutions of higher education in the United States and agriculture. There are over 100 land grant universities in the U.S., from large, well-known universities like Cornell or the University of California, Berkeley to small HBCUs like the University of the District of Columbia. Not only did those land-grant institutions’ original emphasis on agriculture, science, and engineering, create an idea of postsecondary education and research as a resource for everyone, not just elites, but it was through the land grant system that the HBCU system and Tribal College system as we know them now first came into being. In fact, several of our collaborators on the summit and the toolkit came from land-grant universities: April Love from Alcorn State’s Socially Disadvantaged Farmers and Ranchers Policy Research Center, Sakeenah Shabazz from The Berkeley Food Institute at UC Berkeley, Mchezaji Axum from the College of Agriculture, Urban Sustainability and Environmental Sciences at the University of the District of Columbia. Of course, that’s not a history that American University shares. But AU faculty like Garrett Graddy-Lovelace, for example, have been working in collaboration with community partners like the Federation, Rural Coalition, Alianza Nacional de Campesinas, for years – in some cases, over a decade – to build a coalition that connects grassroots movements, farmers and farmworkers, and researchers and scholars. And that’s where the Antiracist Research and Policy Center comes in. From summit to toolkit to our forthcoming online research hub, the “Pointing the farm bill Toward Racial Justice” project is an example of what we believe is the best way toward future social justice: the creation of transformative, scholarship through reciprocal, equitable, and sustainable collaborations among scholars, organizers, and policymakers, presented in ways that are accessible to everyone, including the people most impacted by the issues we address. Not only does it touch on all of our core focus areas – that is, not just climate, land, and environmental justice, but race and reproduction, educational access and equity, and even carceral politics – but it’s an important opportunity for us to remind people that race issues aren’t just urban issues – race is a huge part of the fabric of rural and agricultural American life, and needs to be addressed as such.

This article first appeared on The Daily Yonder and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

-

Over 50 years ago, I switched from a candidate I had endorsed to his opponent (Bob Brown, if anyone cares) two days before the election. Bob and I have remained friends for a long time, and part of the reason is that we both know that my support for any politician is conditional. So long as a politician breathes, he or she has the ability to do something to shaft me, or to stomp the hell out of something I believe in. Ignore the dangling preposition – it’s bad enough that the internet is kicking on and off as I write. I don’t need the ghost of Mrs. Sherman getting new allies in teaching me grammar.

So long as a politician lives, he or she can, and probably will do something reprehensible and let you down. I imagine that Jefferson Davis wasn’t a damned bit surprised when Lincoln introduced the Income Tax – but I suspect that more than a few abolitionist Republicans were absolutely gobsmacked. Just a hunch, you understand.

I’ve had some folks (dedicated democrats) call me a trumpkin. I’ve had MAGA supporters classify me as a libtard. It’s pretty simple – Trump went against my beliefs with the rent controls during the Covid thing. Biden did the same. No taxpayer dares sleep while a politician of whatever side yet breathes. The only politician who can’t roll over and shaft you is a dead one.

Bob is Montana’s closest thing to a good, reliable living politician. He’s retired from that life, so can’t harm anyone. Admitted, we won’t vote the same – he despised Trump more than Hillary, I despised Hillary more than Trump – but that’s really the second stage of responsible voting.

The first stage of responsible voting is voting against the politician who shafted you. I’ll be doing that on Neil Durum. Neil did worse than just shaft Trego taxpayers. He set it up so I will have to vote to raise taxes on my neighbors. He has an opponent – of whom I know nothing – but his opponent has not put me in a spot where I will have to raise taxes for the school because of his vote. Zoey Zephyr voted against the bill – but Neil Durum, who had the opportunity to vote in Trego’s favor chose to vote the other way. Did he even think about what his vote would do, or did he just thoughtlessly vote party line? I don’t know – but responsible voting is voting against a politician – of whatever party – who has voted against you. I’m voting responsibly. I have no problem voting Democrat when a Republican votes against my interests.

Another responsible thought is term limits. Our legislation on term limits can be simplified and improved at the same time. It should be: One term in office, one term in prison. Simple. Elegant. Hell, I even have New York liberals supporting this concept. Admittedly, they only support it if the politician is Donald Trump, but you have to start somewhere.

Vote for the least harmful candidate running – and vote against the candidate who has done you harm. An earlier age used tar and feathers to express disapproval – but that seems a bit messy. For now.

Want to tell us something or ask a question? Get in touch.

Recent Posts

- You Have To Beat Darwin Every Day

- Computer Repair by Mussolini

- Getting Alberta Oil to Market

- Parties On Economics

- Thus Spake Zarathustra – One More Time

- Suspenders

- You Haven’t Met All The People . . .

- Play Stupid Games, Win Stupid Prizes

- The Ballad of Lenin’s Tomb

- An Encounter With a Lawnmower Thief

- County Property Taxes

- A Big Loss in 2025

Rough Cut Lumber

Harvested as part of thinning to reduce fire danger.

$0.75 per board foot.

Call Mike (406-882-4835) or Sam (406-882-4597)

Popular Posts

Ask The Entomologist Bears Books Canada Census Community Decay Covid Covid-19 Data Deer Demography Education Elections Eureka Montana family Firearms Game Cameras Geese Government Guns History Inflation life Lincoln County Board of Health Lincoln County MT Lincoln Electric Cooperative Montana nature News Patches' Pieces Pest Control Politics Pond Recipe School School Board Snow Taxes travel Trego Trego Montana Trego School Weather Wildlife writing