-

Editor’s Note: It always surprises me when I think about it how recently we married and Jedidiah had his introduction to Montana’s wildlife. There’s a little one toddling about with us now when we go for walks, Yoshi has more gray to her muzzle, and my husband is considerably more comfortable with firearms.

But it’s his story- so here is is, as he wrote it for me some years ago:This past week held the anniversary of my moving up to Trego to join my wife, Sam… As such, it also held the anniversary of my meeting the best firearm evangelists I’ve yet encountered.

The bears.

The two delinquent bruins, about a month before I moved up to Trego.

Note the radio collar on the left bear – both have them.A year ago, I wrapped up my Masters Degree project, describing several new species of Kentucky cave beetles, and began the long drive out to Trego, MT. I believe it was the evening of my second day here in Montana that they introduced themselves…

Just as Sam and I were settling in for the evening, we received a panicked phone call from her mother. She was sufficiently agitated for me to hear her some distance from the phone… As it turned out, Sam’s father, Mike, had stepped out onto the porch to shout at couple of gangly young grizzlies, encourage them to get a bit further from his house. But he had a little overweight Pomeranian who had other ideas – she sprinted out the door past him, intent on getting between him and the bears. Despite the size disparity, she startled those bears and made them run… And, as they were running, she pursued them, a good 300-some feet.

Mike couldn’t let her be alone out there with them, so he ducked back inside, grabbed some slippers & the nearest firearm, and headed out after his wee beastie. It’s at this point in time that Sam’s mother called. Sam hurriedly grabbed the keys and produced a couple of guns. She passed me one which I straightaway handed back to her.

At this point in my life, I’d never fired a gun before, and I’m somebody who believes in doing things well. I thought I’d have better combat utility with a walking stick, and took a promising one.

So, off the two of us flew, leaving our own irate wee beastie behind us. Sam at the wheel, bouncing the truck down the old road to her folks. As we arrived the two young delinquent grizzlies were reconsidering their flight from a certain overweight Pomeranian… but they backed off as we raced up in the truck.

Sam passed me her gun, and bailed out to catch the overweight Pomeranian (who refused to get behind Sam’s father), and we retreated back to her folks’ house. While Mike’s seven rounds of 22 weren’t great comfort with two bears at close range… it was a sight better than my walking stick.

The next day we could see the bears from our house, as they enjoyed a neighbor’s water feature. It took about a week for Fish & Game to trap them, and all the while I was waking up to nightmares of bear home invasion. As soon as they were captured and removed from the area, I began learning to shoot. One could scarce ask for better motivation, and I practiced devoutly.

Shortly after our first sighting of grizzlies this year, I had another dream about them staging a home invasion. This time, I was armed, and the dream ended much better for us. While I’d hate to have to shoot one, it’s nice to be capable of doing so, if need be.

-

by Sarah Melotte, The Daily Yonder

May 31, 2024

In a previous article, we addressed the inaccurate assertion that rural voters control a disproportionate share of the U.S. House of Representatives. Today, let’s address the common claim that rural voters wield an unfair share of power in the Senate and Electoral College.

I won’t keep you waiting. They don’t.

People who are worried about unequal representation in the federal government will often cite the small-state bias to support the notion that rural voters have an unfair advantage in the Electoral College and Senate. The small-state bias is the outsized influence states with small populations have in the Senate and Electoral College.

But that argument is based largely on a misunderstanding of what “rural” is. At the state level, rurality is not synonymous with having a small population. While it is true that states with smaller populations have the same number of Senate seats as larger states and a disproportionate share of electoral votes, rurality has nothing to do with it. That’s because most rural Americans don’t live in states that have unequal federal power.

So, what exactly is the small-state bias, and why do people think it benefits rural voters?

What Is the Small-State Bias?

In simple terms, the small-state bias refers to the uneven power that small states wield compared to their larger counterparts. But the precise definition differs based on whether we’re referring to the Senate or the Electoral College.

In the Senate, the small-state bias refers to each state having two senators, regardless of its population size. It doesn’t matter that California’s population exceeds Rhode Island’s population by almost 38 million residents. Both states get two Senate seats.

The small-state bias also affects the Electoral College because a state’s electoral votes are based on its number of seats in the Senate and the House of Representatives. The nation’s smallest states, like Delaware, get a minimum of three electoral votes, one for its single seat in the House, and two for the state’s senators.

But the number of electoral votes a state has is not proportionate to its population. Larger states like Texas have disproportionately fewer electoral votes compared to smaller states like Delaware, exemplifying the small-state bias.

What is rural?

Federal agencies use over a dozen definitions of rural. But at their core, those definitions are generally variations on two predominant categorization systems — one, the OMB’s Metropolitan Statistical Area, which goes down to the county level, and two, the Census definition, which is based primarily on population density. The Census definition subdivides counties down to the census block level, meaning that parts of a county may be rural and other parts urban.

The Census Bureau uses the smallest scale at which we can measure rurality. The census block is about the size of a neighborhood block. The Census definitions, which were revised for the 2020 census, says census blocks with a population of 5,000 residents or 2,000 housing units are urban. Everywhere that is not urban is rural. Using the Census definition, these rural places can range anywhere from an uninhabited desert to a small community.

Because the census definition of rural is the most granular definition available, it captures more detail than other measures. It’s also one of the more generous estimates of rurality that exist, biasing estimates in favor of rural malapportionment.

In the OMB system, metropolitan areas are defined county by county, not down to the census block. The entire county is either metropolitan or it’s not, based on the size of a city in that county or commuting patterns. The OMB considers all other counties to be “nonmetropolitan.”

That might sound unequal, but it’s not due to the rural population in those small states. Predominantly urban states like Delaware and Rhode Island, where rural residents constitute only 17% and 9% of the population, respectively, are also overrepresented in the Senate.

Let’s set aside the Electoral College for now and just focus on the Senate.

Does the Senate Favor Rural Voters?

According to the Census Bureau’s definition of rural, most rural Americans don’t live in a state that has a disproportionate share of senators relative to its population.

That’s because only 43% of rural Americans live in a state with a smaller than average population size, and 29% of the residents in those states are rural, according to the census. A little over a third of the residents in the top 10 smallest states live in areas that the census defines as rural.

Why are we using a different definition of rural?

The Daily Yonder primarily uses the OMB nonmetro definition as a proxy for rural in our analysis because it’s compatible with other monthly and annual datasets from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, USDA, and many, many more.

But in my previous coverage of rural Representation in the House of Representatives, I used the Census definition of rural to analyze voter distribution. That’s because the census doesn’t release data on rural populations at the district level, so I had to estimate rural populations using GeoCorr, an online program created by the Missouri Census Data Center. Geocorr only estimates rural populations using the census definition of rural.

To maintain consistency with our previous coverage of rural politics, I’ll include the OMB rural figures alongside the census figures in dropdown boxes. Click the plus (+) sign at the right of the rectangle to learn more about how the OMB numbers differ from the census numbers.

In other words, the majority of people who benefit from the small-state bias are urban or suburban, not rural.

While rural voters in small states like Delaware, New Hampshire, and North Dakota are overrepresented in the Senate relative to their populations, the urban voters, who make up the majority of residents in those states, are also overrepresented.

Census data shows that only four states have rural majority populations. Those states are Vermont, Maine, West Virginia, and Mississippi. Only 6% of the total rural American population lives in those states. The remaining 94% of rural Americans live in states where the predominant population is urban or suburban.

Are rural voters favored in the Senate according to the OMB definition of rural?

About a quarter of the residents in states with smaller than average population sizes are nonmetropolitan, or rural, according to the OMB system. Compare that to the 29% who are rural in the census definition.

About half of the nonmetropolitan population lives in a state with a smaller than average population, compared to the 43% in the census definition.

Only 8% of nonmetro Americans live in states with majority rural populations, compared to the 6% in the census.

Inequalities in the Electoral College

Most states practice a winner-take-all approach to the Electoral College. In this system, all of a state’s electoral votes go to the presidential candidate who won the popular vote in the state.

Nebraska and Maine, however, practice the congressional district method. In this method, electoral votes go to the winner of the popular vote in each congressional district, while the remaining two electoral votes, representing the two senate seats, go to the statewide winner.

In the congressional district method, electoral votes can be split between candidates if the popular vote varies by district, unlike the winner-take- all method in which all of a state’s electoral votes have to go to one candidate.

Because electoral votes aren’t distributed proportionate to the popular vote, it’s possible that a candidate who won the national popular vote can lose the Electoral College vote, and therefore lose the election.

This happened twice in recent memory. In 2000, Republican presidential nominee George W. Bush lost the popular vote by half a million votes to his Democratic challenger Al Gore, but ultimately won the Electoral College. The event stirred a national controversy that one Guardian reporter called a right-wing coup.

Most recently, a mismatch between the Electoral College and the popular vote happened when, despite losing the popular vote by 2.8 million votes, Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential race against Hillary Clinton.

Critics have rightly pointed out the inequality in the system, in particular how it disenfranchises voters of color. And although the Electoral College system might not be perfect, its inequality is not caused by rural voters.

The Electoral College Bias Is About Small Population, not Rurality

With a population of 39 million residents and 54 electoral votes, California has both more people and more electoral votes than any other state in the nation.

It’s fair that California has more electoral votes than a state like Delaware, which has a population close to one million residents and only three electoral votes. But when we take into account the difference in population size, the numbers don’t come out so evenly.

California has about 0.13 electoral votes per 100,000 residents, while Delaware has about 0.30 votes per 100,000, almost twice as many as California. A perfectly equitable system would give every state the exact same number of votes per 100,000.

But rural voters are not generally the beneficiaries of the system’s bias towards small states. Only 10% of rural voters live in a state that has more than the average amount of electoral votes per 100,000 people.

Approximately two-thirds of the population in these overrepresented states are urban or suburban, not rural. Among the 16 states with more than the average share of electoral votes per 100,000 residents, only Vermont and Maine have majority rural populations. But rural voters in Vermont and Maine constitute only about two percent of the total rural population.

Does the Electoral College benefit rural voters under the OMB definition of rural?

According to the OMB definition of rural, about 14% of rural voters live in states with more than the average amount of electoral votes per 100,000, compared to 10% of rural voters in the census definition.

The OMB figures are the same as census figures regarding the urban populations in states with more than the average amount of electoral votes. In both scenarios, about two-thirds of the populations in these states are metropolitan.

(This article is a follow up to an analysis we published in May, where I deconstructed the myth of rural malapportionment – the idea that rural voters have a disproportionate number of seats in the House of Representatives.)

Daily Yonder reporter Sarah Melotte lives in Western North Carolina and focuses on data reporting.

This article first appeared on The Daily Yonder and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

-

Tuesday’s board meeting began with the rumblings of thunder, which was pretty appropriate. The meeting began with public comment and immediately became heated. It covered hiring policies, touched on old minutes, went into depth about laws governing school board members, and concluded with further details on things that hadn’t been done in properly during the school year. The meeting lasted for more than three hours.

The first comment was by a disgruntled employee, who essentially accused the board of following improper procedures for a contract nonrenewal. While this is something the school board would normally need to discuss in executive session to preserve privacy, an employee has the option to wave that. There were a few interesting points brought up. One was with respect to school authority. In schools without administration, such as Trego, things can get a bit interesting. The employee began with the premise that, since the county superintendent is effectively the administrator for every school in the county that lacks one, the county superintendent of schools should be responsible for performance reviews. The County Superintendent, Suzy Rios was actually present, and was able to clarify that rural schools are somewhat unique. The County Superintendent is confined by law to providing performance reviews for the teachers, not for any other type of employee. She was also able to clarify that the board had been acting in accordance with state law. Another interesting point was made with regards to what a living wage is for the area. As it happens, there’s an online calculator for this. According to it, a single individual without spouse or child, requires around $19 an hour to be making a living wage.

The next public comment was an accusation that two board members had acted inappropriately to give a teacher a raise that was not voted on by the entire board. The board clarified that the board had voted to offer a contract at the previous meeting, and that the salary was determined by the school’s salary matrix. This is fairly standard procedure and Trego School’s matrix was approved a few years ago. Pay is typically determined by a combination of education, years of experience, and licensure. Additional credit hours can result in substantial pay increases. Later in the meeting, the board voted to adopt a salary matrix for classified staff (Eureka’s).

After, the meeting turned to items more formally listed on the agenda. The teachers expressed the desire to do something nice for a guest artist who’d volunteered to work with the kids. Before the board could really begin to consider it, Mark Spehar moved to table it, explaining that he would handle it via a donation. This neatly prevented any need to worry about ethics around spending public funds, and kept the meeting moving smoothly.

Later, the board discussed minutes from August of 2019. The board reversed the 2019 decision that no board member should have keys to the school and designated member Mark Spehar to have a key. It maintained the policy of requiring that paper shredding be approved by the board.

There was a formal discussion of a letter sent to the board- with an explanation from the board that every letter received that way is a matter of public record and should be addressed. The board addressed the letter by paragraph, with some aspects that were quite vague in order to maintain confidentiality as required by law.

Things picked up again, with board chair Nancy Wilkins remarking that while the meeting had already been hard, this next bit would be harder. The board read a formal opinion, received by an attorney from the school board association, about board members acting as volunteers.

“The service as a volunteer must be informal and infrequent to avoid the impression the volunteer service is regularly occurring in a manner that establishes a reliance on the trustee’s service as a volunteer.”

Former board chair, Clara Mae Crawford immediately responded to this. Clara Mae is, of the present board, the most actively involved in the school. Despite this, she’s certainly not the only board member who has been volunteering. School board members have volunteered in many ways: Helping with trash pickup day, arranging the school picnic, teaching the occasional elective class, even having a day a week that a board member would be present at the school.

It had evidently not been clear to the board (and certainly wasn’t clear to me when I ran for school board), that the choice to be on the school board must also be a choice not to volunteer at the school. Clara Mae very succinctly said “I will take the kids over the board. I have more desire to help the kids.”

Following that, there was a discussion of various policies that had been broken, and a bit of debate about what had happened when, if at all.

The meeting concluded with a discussion of the position of district clerk. Superintendent Suzy Rios stated that “District clerk is the hardest job” and “OPI doesn’t care if you’re having a bad day.” The board ultimately determined that due to a massive payroll error, they’d be very limited in what they could do until the error can be corrected. It’s evidently rather severe, since board chair Nancy Wilkins remarked about the need to determine if the school has funds to hire an attorney. When someone asked about the board association attorney, Superintendent Suzy Rios clarified “That’s who told them they’d need to pay for one.” Which ended the discussion.

By the time the meeting adjourned, the rain had let up and the skies were clear.

-

I picked up the mail, and the return address said President Donald J. Trump. Still, the red, white and blue of the stamp, along with the nonprofit org print did a good job of showing me that the letter wasn’t going to be offering any cabinet position.

I wasn’t particularly hurt to find that my letter from Trump wanted me to send a check to the RNC today. I have to admit, I never counted myself so wealthy that the Donald would be sending me a letter asking for a handout. Flattering it is, I suppose, that he calls me a Republican grass roots leader – but I’m already committed to casting my vote in opposition to my local republican representative. Not because he’s a bad person, but because he now has a record of voting against my best interest. Sorry, Donald, but if my “immediate generous support is vital,” my local representative should have considered how voting to screw our local elementary school would affect my political donations and voting patterns.

So, I don’t “stand with you in supporting our Party’s efforts to elect a Republican President, Congress and GOP candidates at all levels.” That doesn’t mean the Republicans have lost my vote – when I weigh the difference between Trump and Biden, I’ll be voting against Biden. The thing is, Biden has done more against my interests. He has a long record, and I’ll be voting against extending that record. But I vote against people who get into office and vote against me.

There’s a certain irony that I received the fund-raising letter on the same day that a New York court convicted Trump of felonies and that the Supreme Court voted 9-0 that Vullo violated the first amendment in coercing various companies to disassociate with the NRA. Anyway you look at it, a 9-0 victory in the Supreme Court, for the NRA, says something bad about New York’s legal system.

I can’t say that Trump’s conviction in New York made me a stronger Trump supporter. In 2016, I voted against Hillary with hopes Trump would be better than her record. He was. In 2020, I voted against Biden knowing Trump would be better than Biden. Again, I figure I was right. I haven’t been given a choice between two younger and better candidates – so I still figure that Trump is a better choice than 4 more years of Joe Biden. It’s the choice I have, not the choice I would dream of having.

-

by Kristi Eaton, The Daily Yonder

May 30, 2024A report from a New York organization says that some low-income rural residents in the state may soon be at risk of losing their homes following the expiration of USDA-financed mortgages that provide protections and rental subsidies to tenants. Money from the state may help repair and rehabilitate some of the buildings, but nationwide, the program is undergoing challenges.

The report shows that as soon as 2027, hundreds of tenants in rural communities in New York will be subject to displacement each year – with limited options for housing and support – as programs begin to lapse. Nationwide, the USDA Section 515 Program has lost more than 150,000 of its original units.

“A lot of these properties are 30 years old and are in need of repair,” Mike Borges, executive director of the Rural Housing Coalition of New York, told the Daily Yonder in a Zoom interview.

“Many of the private landlords who own these buildings have not invested in upkeep. So they’re not in great shape. I think it could be one of the first efforts at the state level to preserve USDA 515 housing.”

The report indicated that New York had approximately 12,000 USDA 515 affordable rental housing apartments, housing about 15,000 low-income seniors and families.

Once the mortgages expire, the owners have the option to leave the program, which comes with rental protections, regulatory protections, as well as rental subsidies that allow people to live there through a rent subsidy and other affordability measures.

The New York State Legislature provided $10 million in state funding to be used for the acquisition of the USDA 515 properties and to rehabilitate them, Borges said.

Established by President Harry Truman in 1949, The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Section 515 Program provided low-cost financing for the construction of affordable multi-family rental housing in rural communities. The USDA program produced 550,000 affordable apartments in rural communities. However, the program has not produced new units in more than 10 years. On top of that, the program has lost more than 150,000 of its original units to reach its current size of less than 390,000 units, according to the recent Multifamily Housing Occupancy Report.

At the Housing Assistance Council, Kristin Blum, manager for the Center for Rural Multifamily Housing Preservation, said the organization agrees with the findings of the report and the urgency to preserve Section 515 properties before the housing resource is lost.

“We hope that the Rural Housing Coalition of New York is successful in their efforts to raise state resources to preserve Section 515 properties,” she added. “Preservation of these properties will require capital investments and states can and should help address these needs.”

Blum said since the start of the Center for Rural Multifamily Housing Preservation two months ago, the focus has been on ramping up technical assistance programs for nonprofits who are acquiring Section 515 properties. Across the country, two-thirds of families and individuals in Section 515 properties are seniors or individuals with disabilities. The average income of tenants is less than $16,000.

“Since March, we’ve added nine nonprofit organizations to our technical assistance program,” she told the Daily Yonder in an email interview. The technical assistance is across the country and will help preserve 500 units of affordable rental housing in California, Georgia, Kansas, Kentucky, Montana, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Utah.

Jonathan Harwitz, director of public policy at HAC, said the USDA’s Section 515 portfolio is a “critical source” of affordable housing in rural communities across America. There is at least one USDA Section 515 property in 87% of all U.S. counties.

“For many rural communities, these 515 units constitute the only affordable rental housing available,” he said.

Yet not all tenants in Section 515 properties receive rental assistance that limits their rent to 30% of household income. Approximately three-quarters of all Section 515 tenant households live in units that are rent subsidized through USDA’s Section 521 Rental Assistance program. Another 15% receive some other help with their rent, such as Housing Choice Vouchers, Project-Based Rental Assistance or HOME program rental assistance administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The remaining 15% receive no rental subsidy, with the result that more than one-third of those unassisted tenants are cost-burdened, he added.

Lance George, director of research and information at HAC, said although the Section 515 program has financed over half a million units since 1963, just over 388,0000 units remain in the program today.

“These units are quickly losing affordability as the mortgages mature or the property is eligible to prepay, putting some of rural America’s most vulnerable residents at risk of homelessness,” he added in an email interview.

This article first appeared on The Daily Yonder and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

-

School’s wrapped up, eighth graders have finished their Montana History trips, and the weather might actually be warm enough to reach some of the higher elevation bits of history. For those of us exploring from armchairs though, it’s time to read about Henry Plummer, and about Edward Stahl if we’re trying to keep the history more local.

When Henry Plummer Ran Montana’s Justice System

On May 24, 1863, the citizenry of Bannack elected Henry Plummer as their sheriff. Henry was personable, had an excellent presentation of self, and was experienced in law enforcement. He had been elected sheriff in Nevada City, California, in 1856. The next year he was convicted of second degree murder, for killing an unarmed man – shades of Derek Chauvin and George Floyd. Henry did six months at San Quentin before California’s governor pardoned him. As I write, Attorney General Merrick Garland is cited “Some have chosen to attack the integrity of the Justice Department,” Garland said Friday…

A Spy on Pinkham Creek

“It was in 1932 that Charlie Powell, ranger at Rexford, overheard a conversation at a trail camp between two Pinkham Ridgers, indicating that the Ridge-runners planned some incendiarism. He promptly reported this to me. The Ridge-runners were a rather canny clan who migrated from the mountains of West Virginia and Kentucky years earlier and took homesteads on Pinkham Creek and Pinkham Ridge. Their chief pursuits were stealing tie timber and moonshining, but occasionally they would set a few fires, “just for the hell of it – to bother the ‘Govment’ men,” and also to provide a few days’…

Edward Stahl at Pipe Creek

Edward Stahl shared a bit about his early days with the Forest Service. This segment starts with his elevation to the Supervisor’s office in Libby. I hadn’t realized that Stahl was a seasonal – I never met a Forest Service seasonal who wound up with a mountain named for him. It looks like he was responsible for the route over Dodge Creek to the Yaak. The whole story is at npshistory.com. I was laid off October 1st and met a party from Eureka and joined them hunting goat at Bowman Lake. We had an early snowstorm and crossed…

Stahl and the 1910 Burn

“Although forty years have passed since the time of the great forest fires in North Idaho the date is not easily forgotten. On August 20, 1910, a forest fire raced unchecked for one hundred miles in two days, to devastate one million acres of wilderness in the Idaho Panhandle and northwestern Montana. Eighty-seven persons perished in the flames and countless numbers of forest creatures were destroyed. If you could see a little black bear clinging, high in a blazing tree and crying like a frightened child you could perceive on a very small scale what happened to the…

-

So you want to attend a school board meeting?

What should you bring?

- Water bottle (possibly two)

- Packed meal and snack (expect an afternoon meeting to go through dinner)

- Travel Pillow (because that afternoon meeting will certainly approach your child’s bedtime, if it doesn’t quite reach yours)

- Seat Cushion (Did you know that sitting for prolonged periods of time can cause sores? Get up and walk around!)

- Watch (if you want to know for sure that it’s taking forever. Skip this if you’d like to just feel this way. The board room has no clock.)

What to know: As a member of the public, you don’t get to comment unless recognized by the board, and board policy limits your public comment to three minutes.

-

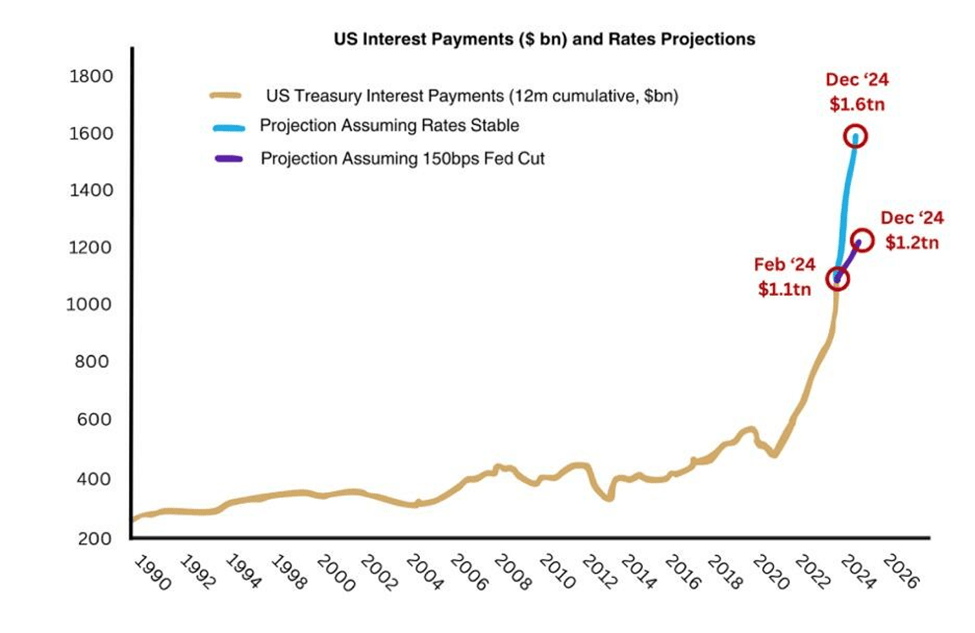

A century ago, our nation’s varied governments – local, state and federal – spent about 4% of the country’s gross domestic product. Now I see a quote that it’s about 36%. To the north, I see that the folks who manage their retirement funds increased that value by 8% – on a playground where things went up by 18%.

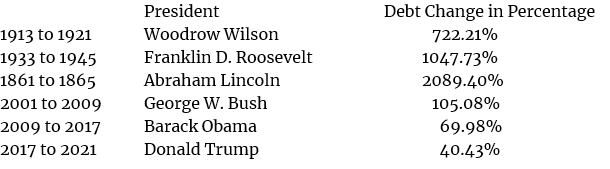

Another comment was a need to return to Reagan’s policies – yet government spending didn’t shrink under Reagan – it just went from being primarily funded by taxes to becoming increasingly funded through borrowing. Here are a few numbers that assign the increase in national debt to a specific presidential administration ( US Debt by President | Chart & Per President Deficit | Self. )

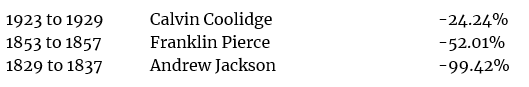

To find an administration where the national debt went down, we have to go back to Calvin Coolidge:

Andrew Jackson almost eliminated the national debt, Calvin Coolidge was the last President to reduce the debt, and Franklin Pierce, at the end of his term, commented “There’s nothing left to do but get drunk.”

It’s easy to spend other people’s money. In five years on the local school board, I’ve watched proposals that required spending taxpayer dollars come before the board for the first time at that meeting and get funded. When I started, I was one that voted that way. After a couple of years, I began to realize – we don’t have many elected leaders like Coolidge, Jackson and Pierce. Too often, we give our elected officials a credit card and let them go ahead.

At the county level, our property values are increasing rapidly – which increases the tax revenues . . . and before that, the main funding for county operation came from timber harvests on the national forest. There’s been a turnover in commissioners – but over most of the years, they’ve spent other people’s money.

Somehow, we’ve avoided sales tax in Montana – but it is moving in with cities like Whitefish adding it first. And it makes sense to the city fathers under the Big Mountain – they’re taxing destination tourists, and getting other peoples’ money. The desire to get a hold on other peoples’ money to spend is great. The desire to manage public funds conservatively is not.

Lincoln County was logically and rationally created in 1909 – the county consisted of a single watershed, traversed by a single railroad line. It was possible to send a postcard from Trego to Libby and get a reply the same day. Things changed when Koocanusa filled – the communities between Jennings Rapids and Douglas Hill were gone. There was no longer the linkage between the county seat at Libby and the North county. Kalispell, not Libby, is the place where Eurekans go to shop.

When Koocanusa filled, Lincoln County’s connections between north and south severed. Fifty years of growth has converted the North County into Libby’s cash cow for operating the county. The only blessing is that we’re not getting as much government as we’re paying for. We can’t expect fiscal responsibility from folks who are spending other people’s money – whether it be Libby, Helena or DC.

It’s time to quit electing nice guys and replace them with penny-pinching curmudgeons.

-

by Lane Wendell Fischer and Olivia Weeks, The Daily Yonder

May 22, 2024Throughout rural America, non-native English speakers are less likely than their urban peers to get proper support in school, sometimes leading to a lifetime of lower educational attainment. But some rural schools are developing multilingual education strategies to rival those found in urban and suburban districts.

In general, it’s easier to fund more diverse course offerings in bigger schools. From Advanced Placement U.S. History to Spanish immersion, more students means more funding. But in rural DuBois County, Indiana, administrators are prioritizing English-learner education. There, students have access to “gold standard” multilingual programming, a hard-won achievement for any U.S. school, but especially for such a small district.

“We are the only school in the region who started a dual language program,” said Rossina Sandoval, Southwest DuBois County School District’s director of community engagement, in an interview with the Daily Yonder.

To meet the gold standard, students in the dual language immersion program receive 50% of their instruction in English and 50% of their instruction in Spanish. Fifty percent of the program is made up of students whose native language is Spanish and the other half is made up of native English speakers. The program is currently offered from kindergarten through third grade, with plans to expand to fourth and fifth grade.

By developing a program with 50/50 language instruction and 50/50 student enrollment, students are able to not only learn both their native and target language from their teachers, but they are also able to learn from each other, Sandoval said.

“That has proven to be the most effective way to develop language skills,” she said.

When the program was first introduced, the school received pushback from both Spanish-speaking and English-speaking families. Spanish-speaking families felt the school should prioritize English learning, given that their children already speak Spanish at home. And English-speaking families worried that they wouldn’t be able to help their children with Spanish homework.

To address family concerns on both sides, the school shared information about the benefits of formal bilingual education. In addition to maintaining their conversational skills, Spanish-speaking students receive instruction in grammar, spelling, and reading in their native language. This approach helps students who already speak another language read and write in another language, too.

Second-grade students in Clinton County’s Bi-Literacy program learn about fruits and vegetables in Spanish. (Photo by Esmeralda Cruz) Learning two languages does not hurt a student’s ability to master either one. Bilingual children are shown to have better focus and logical reasoning, and – according to Sandoval – will be suited to a wider range of opportunities in the workforce.

“It’s natural, we want the best for our kids,” she said. “The best we can do is educate the community as a whole that this is the best method to develop multilingualism, this is the best method to enhance global skills and produce global citizens.”

Intersecting Problems

The Latino population in DuBois County has been expanding for decades. Today it sits at 9.5%, which is approximately half the national percentage. But in Southwest DuBois County schools, more than a third of students identify as Latino. (The disparity in those numbers reflects higher birth rates within the Latino population and the uneven distribution of those families within the county.)

The demographics of rural schools have been changing nationwide. According to a recent report from the National Rural Education Association, 80,000 more English-learner and multilingual students were enrolled in rural districts in the 2021 school year than in 2013.

Historically, rural school districts have struggled to provide high quality education to non-native English speakers. When English-learner populations are small, it can be difficult to fund robust bilingual programming and easy to overlook their necessity.

Rural English learners sit at the intersection of overlapping structural problems in public education. The national teacher shortage is worse in nonmetropolitan places, and it’s most problematic in racially diverse and high-poverty rural schools. Nationally, there aren’t enough bilingual educators, or educators certified to teach English as a second language (ESL).

According to recent research, while English-learner populations are growing in rural places, rural multilingual learners are less likely to receive instruction in their native languages. And while federal guidelines require that all non-native English speakers receive specialized instruction, in rural places only a little more than 60% actually do.

DuBois County’s top-tier bilingual education program should be used as a model in other rural school districts, Sandoval said. “As an immigrant, as a U.S. citizen, I feel very proud… because this can be replicated in communities that look like ours.”

Support for these programs must be built inside and outside the schoolhouse, Sandoval said. “There has to be a degree of openness toward bilingualism or multilingualism.This is an effort that’s not just made by me, it’s made by the school and by the community.”

A third-grade student in Clinton Country’s Bi-Literacy program reviews a lesson about the universe by playing bingo. (Photo by Esmeralda Cruz) Programs that increase accessibility and trust with parents include “Cafe en el Parque,” a parent meeting held in Spanish that draws in over 100 families each month, and the “Emergent Bilingual” program, which meets after school and on weekends helps new immigrant students and families learn more about how the American education system works.

Programs that help establish community support and participation include “Fuertes Together,” a partnership with the public library where families can hear stories in Spanish and English and engage with cultural music, dance, and art. And a new program, “Bilingual Village,” helps bilingual students identify speaking partners in the community who can converse in the student’s new language.

A Wide Range of Strategies

When Esmeralda Cruz was a child in the 1990s, she immigrated with her family from Mexico to rural Clinton County, Indiana, where she lives and works today. “Back then,” she said, “there were not a lot of Latino families in the area. In my first grade classroom I only had one classmate that was bilingual.” This posed major challenges to her education: Esmeralda said that, instead of receiving proper language instruction, she was placed in classes meant to address learning disabilities.

Cruz’s experience is not unique, according to Maria Coady, professor of multilingual education at North Carolina State University. In places that aren’t accustomed to supporting immigrant populations, she’s seen English learners sent to speech therapy in place of proper ESL classes. “Schools might think that all these kids have special learning needs because it looks like they’re not learning,” she said, “when in fact, they’re just learning the language.”

As immigrant populations grow throughout the rural U.S., newcomers often find themselves in Cruz’s childhood position – navigating school districts unaccustomed to educating non-native English speakers.

Today, Cruz works as a Hispanic community engagement director for Purdue Extension. Prior to that, she was the health and human sciences educator at Purdue Extension office in Clinton County, Indiana.

According to scholars of rural multilingual education, schools that do have ESL or bilingual systems in place exist across a broad spectrum, from gold-standard bilingual education programs like the one in DuBois County to ESL sessions that require students to miss part of the school day and provide no native-language instruction.

Hilda Robles instructs fourth-grade students during a lesson in Clinton County’s Bi-Literacy program. (Photo by Esmeralda Cruz) In places with very small English-learner populations, Coady said, schools might pool resources and “bring in an itinerant teacher – that is, a teacher who might travel between several rural schools to provide ESL services.”

This is the least effective method of multilingual education for two reasons, Coady said: it’s disruptive to pull students out of class, and ESL teachers are only able to offer very limited amounts of time to individual students.

Where to Begin?

In rural places, small expansions in local industries that rely heavily on immigrant and migrant labor can create major shifts in student populations, said Holly Hansen-Thomas, professor of bilingual education at Texas Woman’s University. “And these teachers may not have the experience or the background to serve these emergent bilingual families that keep coming to work and to support the industry.”

For rural school districts inexperienced in providing multilingual education, said Hansen-Thomas, professional development is the place to begin.

Federal grants are available to support multilingual certifications for teachers and administrators. For instance, the National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition offers a National Professional Development Program, which makes grants to colleges and universities to fund work on multilingual teaching skills for local educators. Hansen-Thomas also points to the U.S. Department of Education’s “Newcomer Tool Kit,” a resource for rural educators looking to support recent-immigrant students and families.

In Indiana, colleges and universities are attempting to build manageable pathways for multilingual educators who might not be formally trained as teachers. “Our pre-service teachers tend to be white and monolingual,” said Stephanie Oudghiri, clinical associate professor at Purdue’s College of Education. “Especially in the Midwest, as our demographics are changing, we need folks that are multilingual.”

Experts like Cruz stress the importance of listening to non-native English speakers themselves when building out these programs. “We’ve had a lot of focus groups and community conversations and I can’t tell you how many times people at the table have said, ‘Thank you for including me,’” Cruz said.

“I think oftentimes they do want to be at the table, they just don’t know how, and so we’re making sure that we’re listening to them and then going from there, rather than the other way around.”

This article first appeared on The Daily Yonder and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Want to tell us something or ask a question? Get in touch.

Recent Posts

- You Have To Beat Darwin Every Day

- Computer Repair by Mussolini

- Getting Alberta Oil to Market

- Parties On Economics

- Thus Spake Zarathustra – One More Time

- Suspenders

- You Haven’t Met All The People . . .

- Play Stupid Games, Win Stupid Prizes

- The Ballad of Lenin’s Tomb

- An Encounter With a Lawnmower Thief

- County Property Taxes

- A Big Loss in 2025

Rough Cut Lumber

Harvested as part of thinning to reduce fire danger.

$0.75 per board foot.

Call Mike (406-882-4835) or Sam (406-882-4597)

Popular Posts

Ask The Entomologist Bears Books Canada Census Community Decay Covid Covid-19 Data Deer Demography Education Elections Eureka Montana family Firearms Game Cameras Geese Government Guns History Inflation life Lincoln County Board of Health Lincoln County MT Lincoln Electric Cooperative Montana nature News Patches' Pieces Pest Control Politics Pond Recipe School School Board Snow Taxes travel Trego Trego Montana Trego School Weather Wildlife writing