-

US birth rates are at record lows – even though the number of kids most Americans say they want has held steady

More one-and-done families influence the overall birth rate. Maskot via Getty Images Sarah Hayford, The Ohio State University and Karen Benjamin Guzzo, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Birth rates are falling in the U.S. After the highs of the Baby Boom in the mid-20th century and the lows of the Baby Bust in the 1970s, birth rates were relatively stable for nearly 50 years. But during the Great Recession, from 2007-2009, birth rates declined sharply – and they’ve kept falling. In 2007, average birth rates were right around 2 children per woman. By 2021, levels had dropped more than 20%, close to the lowest level in a century. Why?

Is this decline because, as some suggest, young people aren’t interested in having children? Or are people facing increasing barriers to becoming parents?

We are demographers who study how people make plans for having kids and whether they are able to carry out those intentions.

In a recent study, we analyzed how changes in childbearing goals may have contributed to recent declines in birth rates in the United States. Our analysis found that most young people still plan to become parents but are delaying childbearing.

Digging into the demographic data

We were interested in whether people have changed their plans for childbearing over the past few decades. And we knew from other research that the way people think about having children changes as they get older and their circumstances change. Some people initially think they’ll have children, then gradually change their views over time, perhaps because they don’t meet the right partner or because they work in demanding fields. Others don’t expect to have children at one point but later find themselves desiring to have children or, sometimes, unexpectedly pregnant.

So we needed to analyze both changes over time – comparing young people now to those in the past – and changes across the life course – comparing a group of people at different ages. No single data set contains enough information to make both of those comparisons, so we combined information from multiple surveys.

Since the 1970s, the National Surveys of Family Growth, a federal survey run by the National Centers for Health Statistics, have been asking people about their childbearing goals and behaviors. The survey doesn’t collect data from the same people over time, but it provides a snapshot of the U.S. population about every five years.

Using multiple rounds of the survey, we are able to track what’s happening, on average, among people born around the same time – what demographers call a “cohort” – as they pass through their childbearing years.

For this study, we looked at 13 cohorts of women and 10 cohorts of men born between the 1960s and the 2000s. We followed these cohorts to track whether members intended to have any children and the average number of children they intended, starting at age 15 and going up to the most recent data collected through 2019.

We found remarkable consistency in childbearing goals across cohorts. For example, if we look at teenage girls in the 1980s – the cohort born in 1965-69 – they planned to have 2.2 children on average. Among the same age group in the early 21st century – the cohort born in 1995-1999 – girls intended to have 2.1 children on average. Slightly more young people plan to have no children now than 30 years ago, but still, the vast majority of U.S. young adults plan to have kids: about 88% of teenage girls and 89% of teenage boys.

We also found that as they themselves get older, people plan to have fewer children – but not by much. This pattern was also pretty consistent across cohorts. Among those born in 1975-79, for instance, men and women when they were age 20-24 planned to have an average of 2.3 and 2.5 children, respectively. These averages fell slightly, to 2.1 children for men and 2.2 children for women, by the time respondents were 35-39. Still, overwhelmingly, most Americans plan to have children, and the average intended number of children is right around 2.

So, if childbearing goals haven’t changed much, why are birth rates declining?

What keeps people from their target family size?

Our study can’t directly address why birth rates are going down, but we can propose some explanations based on other research.

In part, this decline is good news. There are fewer unintended births than there were 30 years ago, a decrease linked to increasing use of effective contraceptive methods like IUDs and implants and improved insurance coverage from the Affordable Care Act.

Compared with earlier eras, people today start having their children later. These delays also contribute to declining birth rates: Because people start later, they have less time to meet their childbearing goals before they reach biological or social age limits for having kids. As people wait longer to start having children, they are also more likely to change their minds about parenting.

But why are people getting a later start on having kids? We hypothesize that Americans see parenthood as harder to manage than they might have in the past.

Although the U.S. economy overall recovered after the Great Recession, many young people, in particular, feel uncertain about their ability to achieve some of the things they see as necessary for having children – including a good job, a stable relationship and safe, affordable housing.

At the same time, the costs of raising children – from child care and housing to college education – are rising. And parents may feel more pressure to live up to high-intensive parenting standards and prepare their children for an uncertain world.

And while our data doesn’t cover the last three years, the COVID-19 pandemic may have increased feelings of instability by exposing the lack of support for American parents.

For many parents and would-be parents, the “right time” to have a child, or have another child, may feel increasingly out of reach – no matter their ideal family size.

Sarah Hayford, Professor of Sociology; Director, Institute for Population Research, The Ohio State University and Karen Benjamin Guzzo, Professor of Sociology and Director of the Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

-

Friday morning came, and with the second cup of coffee I saw a snow goose flying in from the east, pursued by a bald eagle. When we lived in the flyway it was fairly common to see a snowgoose knocked from the sky by an eagle – but here, with the ponds, the eagle attacks on geese are at the close-up level.

The bald eagle wasn’t my resident eagle – this one was a lot larger. I’m making the guess that the snow goose was flying east of us, and Dickey Lake was still ice-covered the day before – so, under attack in the sky, the goose headed west. The eagle didn’t give the goose enough space to land on the circle pond. They crossed the pond by Fortine Creek Road, and the goose made its own luck, cut back 180 degrees and plummeted into the midst of a dozen goldeneyes on the pond.

After that we watched the eagle attempt to dive past the goose and grab – at least 30 times, each time unsuccessful. I hadn’t realized that a highly motivated goose can dive almost as well as the small ducks. It was quite a show – but life or death for the goose. After the eagle finally left the Snow seems to have decided to buddy up with the Canadian – a single white goose with a black stripe, grazing with the Canadians that are just beginning to nest.

The first goose lost to an eagle in front of us was one with angelwing – the little guy could almost fly, maybe 50 yards or so, but couldn’t leave for the winter. Almost made it through until Spring – we had left the aerator on to keep a little open water, and the Canada goose could camp under the footbridge – but when the Golden Eagle caught it out in the open it didn’t have much chance.

I can find a lot of pictures where the eagle won – but somehow I couldn’t quit watching to go for a camera while I watched the snow goose get away.

-

I’ve revised my perspective on nasty side-effects of COVID. It isn’t that some of the listed side effects of the disease or its vaccinations are suddenly sounding like a lot more fun, it’s that I recently read about someone who acquired my own personal tragedy via Covid-19.

I’ve been faceblind for almost a decade, and while there’s probably a lot about my brain injury that could be considered objectively “worse”, the worst thing for me to deal with has been my inability to recognize the people I love.

I am profoundly faceblind. I cannot recognize my parents, nor my husband, nor even my own reflection. I will never recognize the son we’ve recently been blessed with.

So I was horrified to see an article out of Dartmouth- the place in the US for studying faceblindness (prosopagnosia)- that described someone acquiring faceblindness via covid.

The folks at Darmouth have some very good online tests for facial recognition, if you’re curious. Facial recognition is a spectrum, from the very bad (me) to the very good (people who never forget a face). If you’re like me, I’d recommend outsourcing the task; mine is done by a Pomeranian.

-

It’s a 4-year-old publication – but J P Konig worded things better than I can: “What is the U.S.’s greatest export? Banknotes. There is probably no other product for which the balance of trade is so tilted in the U.S.’s favour. No foreign bills circulate in the U.S., but U.S. bills are eagerly used all over the world.

According to the Federal Reserve, there are currently $1.74 trillion paper dollars in circulation. How many of these notes circulate in the U.S. and how many are used overseas?

Because banknotes cannot be tracked, this question is particularly difficult to answer. This blog post explores several approaches for determining the location of notes. These approaches offer a wide range of estimates, from as low as 40% of all currency being held outside of U.S. borders to as high as 72%.”

bullionstar.comThe problem is, Trump ran the printing presses like crazy, and under Biden our government’s fiscal policy seems to have been to show Trump was a piker. Since Nixon did away with the gold standard, the US dollar has been the world’s currency. In South America, I learned to tip in Yankee dollars – they were much more appreciated by the waiters. Not everyone stashes their reserves in Ben Franklins. To the folks at the bottom, that single with a picture of George Washington became an emergency reserve. Panama, Ecuador, and El Salvador are nations that don’t have their own currency – they operate on the US dollar.

“The top 20 currencies in use today are the US Dollar, Euro, British Pound, Japanese Yen, Chinese Yuan, Canadian Dollar, Australian Dollar, Swiss Franc, New Zealand Dollar.

The US dollar is the most widely used currency around the world. It is followed by the Euro as well as the British Pound which are also used globally. The Japanese Yen is utilized by a handful of countries including Japan and China. In contrast, the Chinese Yuan is only used in China and Canada. Finally the Swiss Franc can only be used in Switzerland.

What Are Some of the Best Alternatives to the USD The US dollar is at present one of the world reserve currency currency, which is the most used currency in the world.

This position has been contested by nations like China as well as Russia. Both of them have implemented their own currencies to replace the USD.

Russia and China aren’t the only countries that have taken action to take on US dominance over currency. Other countries like Iran, Turkey and Venezuela have also adopted their currency as an alternative to the USD.”

cyber.harvard.eduI don’t expect all of those C-notes to come home – the other currencies have their own inflationary problems, so aren’t a perfect replacement. But loonies and toonies don’t exchange readily in South Dakota or Nebraska – and Canada is an alternate reserve currency. Here I can spend Canadian currency. I can’t spend yen. Our inflation has been mitigated by the dollars that leave the US – but we really can’t afford having them come home. If 72% of US currency is outside the US borders, and just 28% returns, we’re looking at 100% inflation – inflation we escape when we maintain the greenback as the world’s default currency.

The Daily Hodl has an article titled “New Global Currency Designed to Ditch US Dollar Coming From BRICS Nations: Report.” it starts with this

A group of economically-aligned nations plan to create a new currency that could reduce the world’s dependence on the US dollar and the euro, according to a new report.

The group of emerging economies, known collectively as BRICS, are exploring how such a currency would be structured, reports the Russian state-owned news agency Sputnik.

The new dollar alternative could be backed by gold, additional rare earth metals or something else entirely, says State Duma Deputy Chairman Alexander Babakov.

“The transition to settlements in national currencies is the first step. The next one is to provide the circulation of digital or any other form of a fundamentally new currency in the nearest future.

I think that at the coming BRICS Summit, the readiness to realize this project will be announced. Such works are underway.”

We may look back on the Jimmy Carter years as years of enlightened economic policy.

-

Feral pigs harm wildlife and biodiversity as well as crops

Wild boar in a swamp in Slidell, Louisiana. AP Photo/Rebecca Santana Marcus Lashley, Mississippi State University

They go by many names – pigs, hogs, swine, razorbacks – but whatever you call them, feral pigs (Sus scrofa) are one of the most damaging invasive species in North America. They cause millions of dollars in crop damage yearly and harbor dozens of pathogens that threaten humans and pets, as well as meat production systems.

As a wildlife ecologist, I am interested in how feral pigs alter their surroundings and affect other wild species. In a recent study, members of the lab I directed through mid-2019 at Mississippi State University showed that wild pigs are a serious threat to biodiversity.

Using trail camera surveys to monitor 36 forest patches between 10 and 10,000 acres in size, we determined that forest patches with feral pigs had 26% less-diverse mammal and bird communities than similar forest patches without them. In other words, many wildlife species seem to be excluded from areas where pigs are present.

This finding is concerning because feral pig populations, which have been present in North America for centuries have rapidly expanded over the past several decades. Recent studies estimate that since the 1980s the pig population in the United States has nearly tripled and expanded from 18 to 35 states. They also are spreading rapidly across Canada. https://www.youtube.com/embed/KmARFWfJT_k?wmode=transparent&start=0 Farmers and scientists describe damage from wild pigs in Missouri.

Omnivores on the hoof

Much concern over the spread of feral pigs has focused on economic damage, which was estimated in the early 2000s at about US$1.5 billion annually in the United States. Since then, feral pig populations in the U.S. have grown by about 30% and the area they occupy has expanded by about 40%, so their economic impact likely has increased.

Feral pigs have a unique collection of traits that make them problematic to humans. When we told one private landowner about the results from our study, he responded: “That makes sense. Pigs eat all the stuff the other wildlife do – they just eat it first, and then they go ahead and eat the wildlife too. They pretty much eat anything with a calorie in it.”

More scientifically, feral pigs are extreme generalist foragers, which means they can survive on many different foods. A global review of their dietary habits found that plants represent 90% of their diet – primarily agricultural crops, plus fruits, seeds, leaves, stems and roots of wild plants.

Feral pigs also eat most small animals, along with fungi and invertebrates such as insect larvae, clams and mussels, particularly in places where pigs are not native. For example, one recent study reported that feral pigs were digging up eggs laid by endangered loggerhead sea turtles on an island off the coast of South Carolina, reducing the turtles’ nesting success to zero in some years.

And these pigs do “just eat it first.” They compete for resources that other wildlife need, which can have negative effects on other species.

However, they likely do their most severe damage through predation. Feral pigs kill and eat rodents, deer, birds, snakes, frogs, lizards and salamanders. This probably best explains why the decrease in diversity we observed was similar to other studies of invasive predators. And our findings are consistent with a global analysis showing that invasive mammalian predators – especially generalist foragers like feral pigs – that have no natural predators themselves cause by far the most extinctions.

Altering ecosystems

Many questions about wild pigs’ ecological impacts have yet to be answered. For example, they may harm other wild species through indirect competition, rather than eating them or depleting their food supply.

In one well-known case, feral pigs indirectly caused the near extinction of indigenous foxes on California’s Channel Islands. The pigs were released on the islands over 150 years ago, but did not apparently affect fox populations for over a century. That changed when golden eagles began breeding on the islands in the mid-1990s, after hunting and exposure to the insecticide DDT eliminated bald eagles, which were golden eagles’ natural enemy.

Unlike bald eagles, which eat mainly fish, golden eagles hunt on land. Wild pigs served as easy prey for them allowing the eagles to become established. The eagles also ate island foxes, and nearly eradicated them as a result.

Ultimately the foxes were restored through an elaborate initiative. First, wildlife managers removed pigs from the islands. Then they restored bald eagles to ward off the golden eagles. Finally, managers reintroduced foxes that had been raised through captive breeding.

Feral swine damage native habitats by rooting up grasses and rubbing on trees. Their activities can create opportunities for invasive plants to colonize new areas. USDA APHIS, CC BY Another major concern is feral pigs’ potential to spread disease. They carry numerous pathogens, including brucellosis and tuberculosis. However, little ecological research has been done on this issue, and scientists have not yet demonstrated that increasing abundance of feral pigs reduces the abundance of native wildlife via disease transmission.

Interestingly, in their native range in Europe and Asia, pigs do not cause as much ecological damage. In fact, some studies indicate that they may modify habitat in important ways for species that have evolved with them, such as frogs and salamanders.

So far, however, there is virtually no scientific evidence that feral pigs provide any benefits in North America. One review of feral pig impacts discussed the potential for private landowners plagued with pigs to generate revenue from selling pig meat or opportunities to hunt them. And it’s possible that wild pigs could serve as an alternative food source for imperiled large predators, or that their wallowing and foraging behavior in some cases could mimic that of locally eradicated or extinct species.

But the scientific consensus today is that in North America, feral pigs are a growing threat to both ecosystems and the economy.

[ Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter. ]

Marcus Lashley, Assistant Professor of Wildlife Ecology, Mississippi State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

-

There is a lot of information available – perhaps just the amount of available information is so great that it keeps us from using data in deciding what to do. There is an article titled “Nine Ignored Trends That Will Shape The Future” at this link.

I turn the radio on when I drive – usually I settle for the bird sounds at home, interrupted by BN’s trains a mile away, or vehicles along Fortine Creek Road. I can’t make it to Kalispell without hearing a kindly physician voice explaining why we won’t provide opioids to people in pain . . . and I think how fortunate I was to go through colon cancer before this ban – and the trends article shows this graph:

The explanation doesn’t address the prescription drug overdoses the radio physician describes:

“1. The Silent Fentanyl Pandemic

• Overdose is the leading cause of death in under 45’s (Replacing suicide)

• Covid killed 8,900 young people in 2020. Overdoses killed 49,000. (2/3rds Fentanyl)

• In 2022, police seized enough Fentanyl to kill every adult and child in America”If two thirds of the overdose deaths are Fentanyl, those ad dollars aren’t going in the right place.

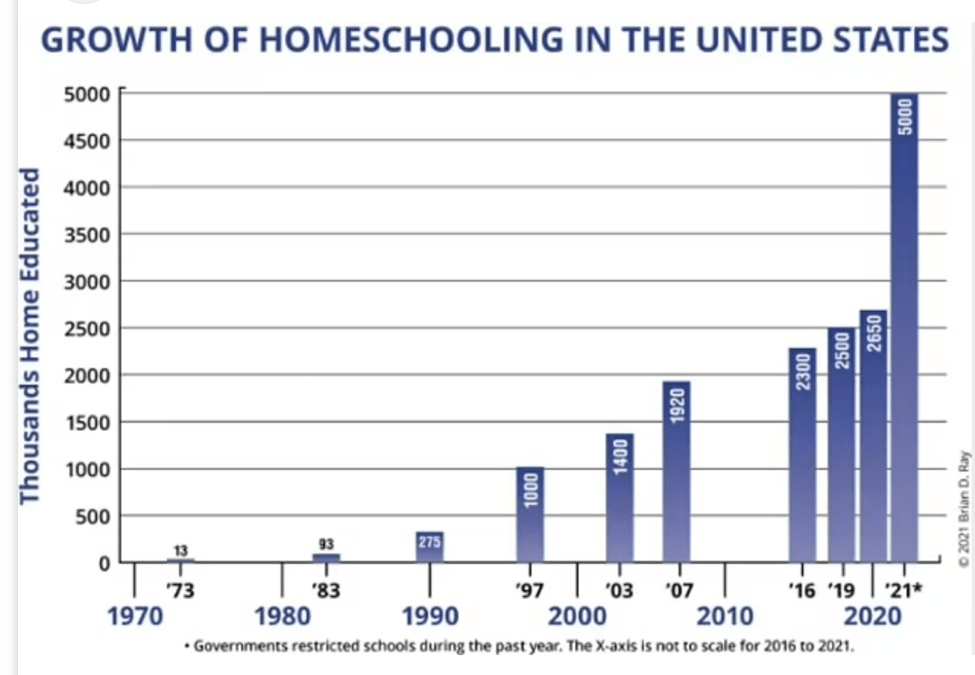

I’m on the local school board. If anyone ever tells you it’s a thankless job, they’re right. The link has a couple of charts that demonstrate spots where it looks like public education isn’t dealing with the trends:

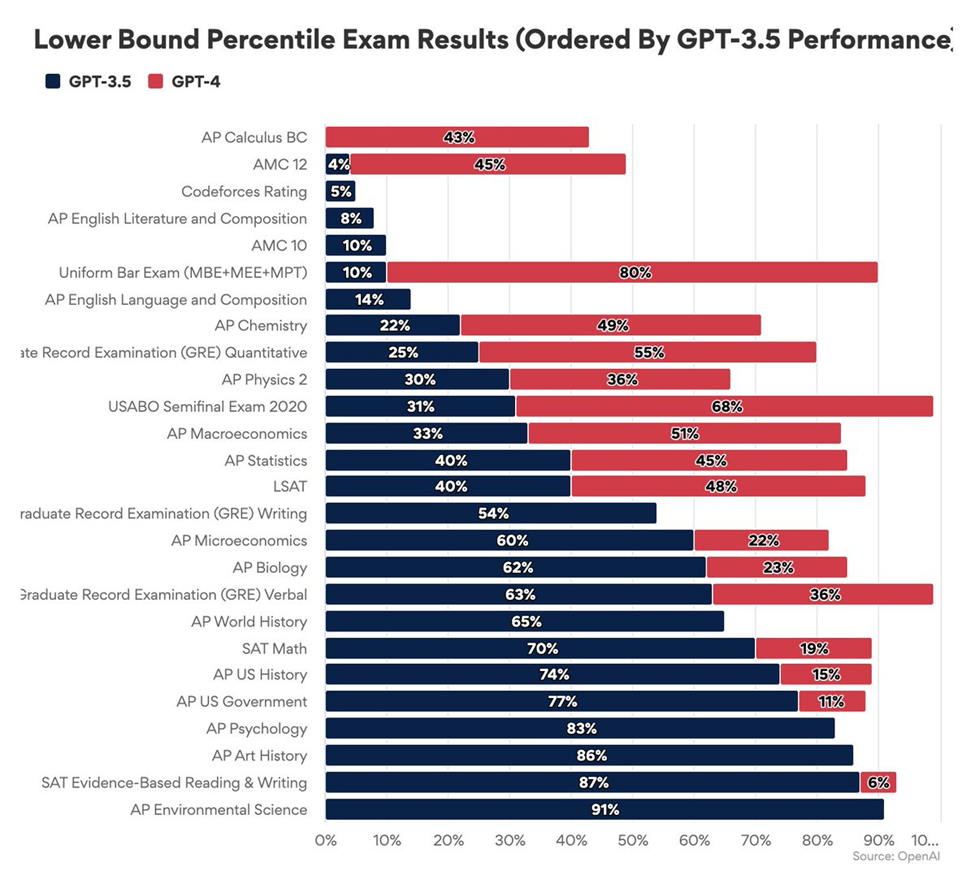

There are more, ranging from demography and fertility through economics. It’s worth clicking the link and spending a couple of moments thinking about where the trends are heading. Fentanyl isn’t a concern to me. I think I can explain the decline in GRE scores by citing the increased enrollment in graduate schools – and I recall that ten years ago, I listened to a presentation lauding the fact that 56% of our high school graduates were headed to college . . . that superintendent never wondered why 6/56ths (10.7%) of our college bound high school graduates were below the mean.

-

Years ago, I ran across a parody of Stephen Covey’s book Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. The Parody title was Seven Habits of Highly Effective Pirates – and I learned on schlockmercenary that it has been expanded, and republished under the new name of Seventy Maxims of Maximally Effective Mercenaries. Apparently the author encountered a copyright infringement problem:

Behind the Scenes

The book was originally called The Seven Habits of Highly Effective Pirates, but in January 2011, Howard Tayler received a cease and desist letter from Franklin Covey, stating that Franklin Covey has a trademark on the phrase “7 Habits”. Tayler then edited all dialog in the strip that mentioned the book’s title or its rules, in what he called the Great Retcon of 2011.

The first maxim is “1. Pillage, then burn.” That makes sense for both pirates and mercenaries. The 11th maxim is “11. Everything is air-droppable at least once.” I think that one came out of the old horse traveling days – I was young when I first heard it stated – “You can shoot from the back of any horse – ONCE.” The old-timer who explained that to me probably first heard that maxim in the 19th century.

Maxim 41 sounds like something I heard from IT when the computer wasn’t functioning: “Do you have a backup? means I can’t fix this.”

Finally, Maxim 70: “Failure is not an option – it is mandatory. The option is whether or not to let failure be the last thing you do.”

-

It’s my grandfather’s fault – Dad told of his father’s 410 pistol, and how it had disappeared from the house the day of the funeral. Even if it had not been disappeared, Dad would have been unlikely to keep it – he was too young when his parents died, and the second World War with a career of sea duty stood between him and a spot to keep his father’s gun.

Today, there are a lot of 410 pistols. There were few in the thirties, when his father’s pistol disappeared (and even fewer in the 80’s when I started looking for one for Dad). My first research was flawed – I thought my grandfather’s gun was possibly a Marvel Game Getter. In those pre-database days, not realizing the manufacturer was Marble, not Marvel, set the research off to a poor start. Today, the research is a bit easier – and shows that there just wasn’t a way Dad could have kept his father’s pistol.

“The legal woes of the Game Getter

The originals were made with 12-, 15-, and 18-inch barrels. The National Firearms Act of 1934 made all of the game getters with smooth bores illegal. While the Feds were trying to curtail the use of short-barreled shotguns by criminals (at least that was the justification given to the public), they managed to kill the Game Getter and some other really useful pocket shotguns. In 1939, in what seems like a very rare circumstance, the ATF revised its ruling on the 18-inch Game Getter and removed it from the prohibited firearm list. The 12-inch and 15-inch are still too dangerous for common folk like us to handle.”

https://www.gunsamerica.com/digest/closet-classic-review-marbles-game-getter-gun/From Dad’s description, I figured the missing gun must have had a 12-inch barrel, looking something like this:

The advertisement where I got the photo explained “Double-barrel (over-under) combination gun with a skeleton folding stock. 22 rimfire rifle barrel over a 44 smooth bore shotgun barrel. This is the 12″ barrel model and requires class III OAW transfer.” Two pieces of information – it was a class 2 restricted ‘Any Other Weapon’ – and it was a 44 smooth bore. That second piece of information directed me toward researching the origins of the 410 cartridge.

That led to the Harrington & Richardson Model 1915 – marked for 410, 44WCF, and 44 XL Shot shell Only – in those early days, they hadn’t standardized the cartridge as a 410 – the old 44 Winchester shells, loaded with shot, were still the norm.

At jefenry.com I found more information:

“A few years ago, my uncle gave me my great grandmother’s old Stevens Model 101 44-Shot. The barrel is 26 1/8″ long and it’s chambered for the .44-40 shot cartridge, although ball cartridges could also be used. The gun is a single shot tip up action and the lever on the bottom opens the breech and also serves as the trigger guard. These guns were made from 1914 to 1920.

The 44 shot was mainly used in America, while the .410 (12mm) was used in Europe. Eventually the .410 caught on and the .44 shot fell into disuse. There’s no commercially available ammunition for the gun since it’s an obsolete caliber, but there is a way to make your own.”

Check his page – there is some good information there on other topics.

So my research continued – a long century ago, they were using cartridges labeled 410, 12mm, and 36 gauge in Europe, while in the US we were moving from 44 shot to 410.

So Fiocchi is still selling 410 ammunition as 36 gauge in Europe. That tidbit of knowledge answered a question from before I turned 10 . . . my mother’s uncle Albert kept a 36 gauge in the barn to shoot magpies, and I never realized that it was an old European shotgun with the gauge markings from Europe.

My first attempt at a 410 pistol for Dad was in the seventies – A Thompson Center Contender, chambered for 45 Colt, rechambered for 3-inch 410 cartridges, and with a removable choke. He didn’t like it – said it kicked too much – but it started me researching how the 410 got its name.

-

I didn’t want to take martial arts lessons. In fact, I think I went so far as to cry about it when Dad insisted I did.

After I learned how to throw people (which might be a better way to teach fulcrums and levers than anything I’ve ever tried with a high school physics class), I changed my tune and more or less hung on my teacher’s every word.

One of the notions my teacher tried very hard to instill was the idea of a fair fight. Dad objected, strenuously, which was odd for him since he was generally on board with whatever I was learning in martial arts.

In the end, Dad’s basic premise was that there was no such thing, and that trying to arrange one was just going to ensure it was unfair in the other person’s favor.

I’d like to say that I understood that quickly, but it really took the idea of “God made men, Samuel Colt made men equal”, combined with a growing appreciation for sexual dimorphism to get the point across. By high school it was fairly obvious that martial arts or not, I wasn’t likely to find myself in a fair fight with the male of the species.

As I’ve gotten older, it’s become apparent that conflict is seldom fair. Resources and ability are not evenly distributed, whether the forum is physical or cognitive.

If fair is at best a description of the weather, it’s unhealthy and irresponsible to teach our children to handicap themselves seeking it, and a worse thing to teach them to expect it.

-

After a rather lengthy NICU stay (umbilical cord around the neck three times, and a failure to realize that breathing has to be continual), we’ve finally returned home and everyone is doing well. The Mountain Ear will be resuming the usual schedule- check for us on Tuesday mornings.

Want to tell us something or ask a question? Get in touch.

Recent Posts

- Watching Iran

- The Quality of Numbers

- Robert Treat Payne Had Traveled To Greenland

- 75 Years Ago in New York

- Recovery Time for a Retiree

- Venn Diagram and DSM

- When Castro Was Cool

- You Have To Beat Darwin Every Day

- Computer Repair by Mussolini

- Getting Alberta Oil to Market

- Parties On Economics

- Thus Spake Zarathustra – One More Time

Rough Cut Lumber

Harvested as part of thinning to reduce fire danger.

$0.75 per board foot.

Call Mike (406-882-4835) or Sam (406-882-4597)

Popular Posts

Ask The Entomologist Bears Books Canada Census Community Decay Covid Covid-19 Data Deer Demography Education Elections family Firearms Game Cameras Geese Government Guns History Inflation life Lincoln County Board of Health Lincoln County MT Lincoln Electric Cooperative Montana nature News Patches' Pieces Pest Control Politics Pond Recipe School School Board Snow Taxes Teaching travel Trego Trego Montana Trego School Weather Wildlife writing